Human beings often long for certainty, but deductive certainty is not generally available to us outside of narrowly formal domains like mathematics and logic. Deduction can show us what follows from what—if the premises are granted—but it cannot itself supply the premises or guarantee to fallible minds their truth. In practical life, we rarely possess indubitable first principles from which to derive conclusions with necessity. The world resists such closure: our experiences are fragmentary, our observations limited, and the future never guaranteed to mirror the past. If we demand deductive certainty before forming expectations, we end up paralyzed.

Yet human cognition has not been powerless. Across medicine, physics, and daily survival, we rely on a different mode of reasoning: induction. Inductive inference operates by projecting patterns from past observations into the future, weighting hypotheses according to their demonstrated success, and adjusting expectations as evidence accumulates. This procedure lacks deductive inevitability, but its power is precisely that it calibrates our beliefs to performance.

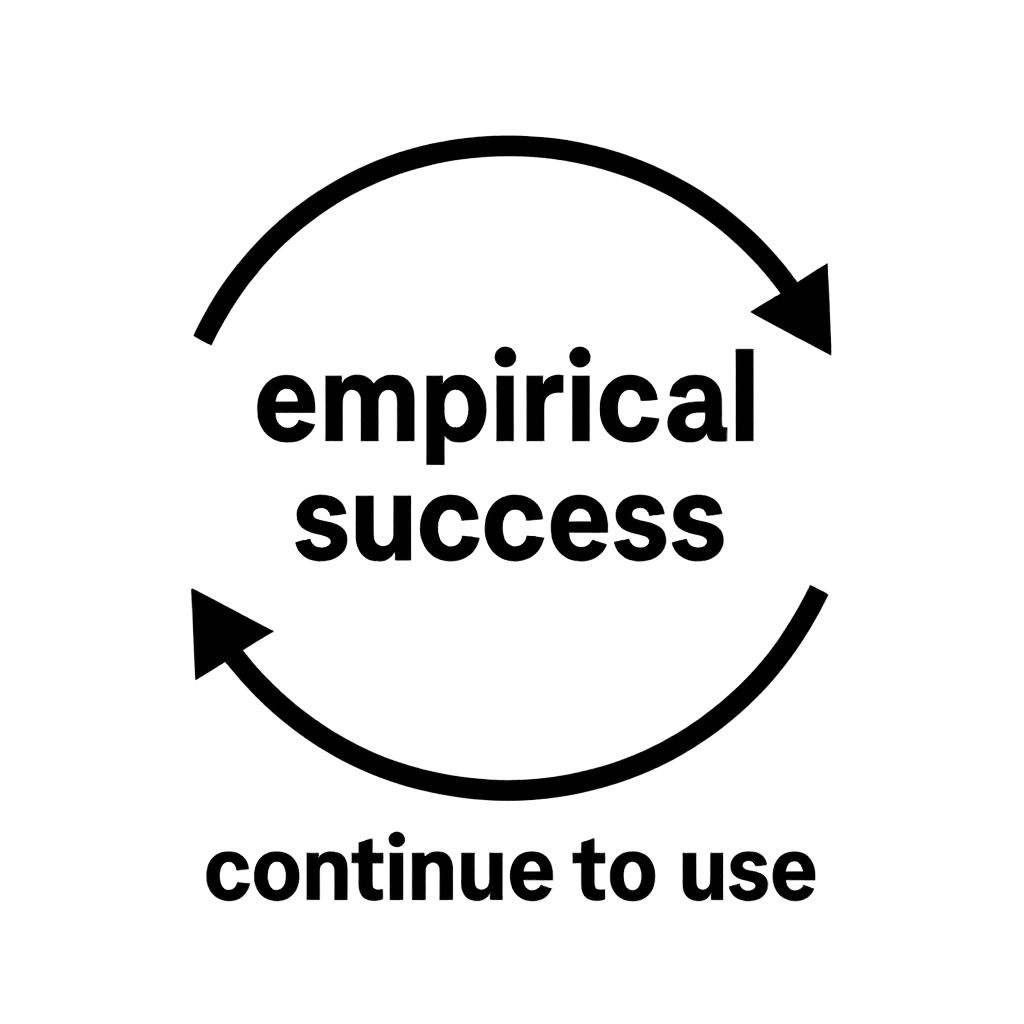

The schema proposed—“to the degree and for as long as X works, let X inform your expectations”—captures the self-substantiating character of induction. Unlike dogmatic faith, which persists regardless of counter-evidence, induction ties its own continuation to its track record. If it ceases to guide us successfully, it will, by its own rule, be abandoned. If it continues to yield predictive and explanatory success, then continuing to rely on it is nothing more than following what works. The alternative—preferring methods that demonstrably fail—is not just unproductive but epistemically incoherent.

Thus, while deductive certainty is beyond the reach of finite human minds, induction offers a rationally defensible way forward: a method that justifies itself not by circular decree but by its sustained capacity to deliver reliable expectations in a world where survival and flourishing depend on anticipating what comes next.

◉ Formalization

1) Vocabulary and primitives

(empirical average loss up to

.)

(M works to degree λ by time t.)

(No appeal to “moral” or categorical ‘oughts’; the bridge is instrumental: lower loss → better choice.)

2) The meta-rule X and its self-application

This is rule-circular but not vicious: the criterion is performance, externally checkable via loss. The rule does not assume its own reliability; it tests it and continues using it if and only if the tests keep favoring it.

3) Inductive bridge from observed performance to expected performance

Proper scoring → lower observed loss is unbiased evidence of higher predictive quality; (IP) formalizes the law-of-large-numbers convergence that makes the evidence cumulative.

4) Pragmatic vindication of induction (against “following what does not work”)

Let encode an inductive method (e.g., Bayesian updating with a regular prior).

(You can weaken “dominance” to “no-worse asymptotically across a wide class.”)

Then:

So, to the degree continues to win empirically, for as long as it does,

keeps selecting

. Preferring a strictly worse performer

when

violates your instrumental bridge and is simply irrational under your own criterion.

5) No-regret guarantee (safety of “follow what works”)

Let the regret of a policy be:

If is implemented via any standard no-regret selection (e.g., Hedge/Weighted-Majority over

):

Thus is safe: asymptotically it does no worse than the best fixed competitor and tracks whichever method “works.” If induction

is that method,

asymptotically behaves like

.

6) Fixed-point (self-substantiation) analysis

Define a monotone operator on policies:

On the complete lattice of policies ordered by pointwise loss, has fixed points by Tarski.

Interpreting as your

: it selects itself exactly when it empirically outperforms rivals; otherwise it switches. The self-reference generates stability under success, not vicious justification.

7) Fitch-style skeleton showing non-viciousness

Step 4 shows the conditional structure: use if it works; nothing in the derivation assumes

is reliable a priori. When

, the same form holds: if

works, keep using

; if not, stop — benign rule-circularity.

8) Direct formalization of your sentence-schema

Let the schema be the unary predicate on rules :

Self-application sets R=XR=XR=X where is defined by Φ\PhiΦ. Then:

This is a fixed-point by definition, not a petitio principii: the justificatory weight is carried by (empirical success) plus the instrumental bridge from success to selection.

9) Bottom line

- Your rule

(“follow what works, to the degree and for as long as it works”) is self-substantiating in a pragmatic sense: it selects itself exactly when its empirical performance warrants it, and abandons itself when it doesn’t.

- Under minimal inductive assumptions ((IP) + proper scoring), empirical success converges toward expected success; selecting the lower-loss method is instrumentally rational.

- Preferring a worse performer is flatly irrational by your own bridge from loss to expectation. That’s the “proof” you asked for: it’s not a deductive proof of induction; it’s a deductively formalized vindication by performance that is self-consistent, non-viciously rule-circular, and decision-theoretically safe.

◉ A Plain English Walkthrough

1) Vocabulary and primitives

We set up the basic building blocks:

- Time is broken into steps.

- At each step, outcomes happen, and methods (rules of inference) make predictions.

- We can score how well each method performs by using a loss function, which measures the error between predictions and actual outcomes.

- The average loss up to a given time is our measure of how well a method has been working.

- A method is said to “work” to some degree if its average loss stays below a certain threshold.

2) The meta-rule and its self-application

We define a master rule, call it X: At each time, choose the method with the lowest average loss so far.

X can even be applied to itself — if it works better than alternatives, it keeps choosing itself. If it doesn’t, it switches to a better method.

This is self-referential but not viciously circular, because it bases the decision only on observed performance.

3) Inductive bridge from observed performance to expected performance

The principle of induction says: if a method has performed well so far, then it is reasonable to expect it will continue to perform well.

Formally, the average observed loss converges toward the true expected loss as more data comes in.

So, using the method with the lowest observed loss is justified, because lower past loss is good evidence of lower future loss.

4) Pragmatic vindication of induction

Let I represent an inductive method (e.g., Bayesian reasoning).

Induction is pragmatically superior because, in the long run, its performance is at least as good as any alternative method, across a broad range of possible data-generating processes.

Therefore, as time goes on, induction will continue to be chosen by rule X, since it consistently outperforms competitors.

Choosing a worse-performing method instead of induction would be irrational by your own standards of success.

5) No-regret guarantee

We can measure regret: the difference between how well a chosen method has done and how well the best possible method would have done.

If we follow rule X with a no-regret algorithm, our regret per time step goes to zero in the long run.

That means X is safe: over time it will do no worse than the best fixed method, and it will track whichever method is performing best. If induction is best, X will end up behaving like induction.

6) Fixed-point (self-substantiation) analysis

We can treat X as an operator that picks the best-performing method.

On the space of all possible policies, this operator has fixed points (points that map to themselves).

That means there exist rules that keep selecting themselves whenever they are the best performers.

Interpreting this fixed point as X: it selects itself exactly when it works, and abandons itself otherwise. This self-reference is stable and not vicious.

7) Fitch-style skeleton showing non-viciousness

This section lays out the reasoning in a structured, proof-like style:

- If a method works to a given degree, then it is selected.

- Induction currently works.

- Therefore, induction is selected.

- From 2 and 3, we can show that if induction works, then it will be selected.

- By inductive principles, induction keeps working in the long run.

- Therefore, induction will keep being selected.

- Thus, induction is consistently chosen under the meta-rule.

The conclusion: using induction under rule X is not circular but justified by its success.

8) Direct formalization of your sentence-schema

We capture your principle formally:

“To the degree and for as long as a method works, let it inform your expectations.”

Applied to X itself, this becomes: if X works, then X informs expectations.

This is a fixed-point: it sustains itself when it performs well, and drops away if it doesn’t. It doesn’t assume what it tries to prove; it bases everything on performance.

9) Bottom line

The master rule X is self-substantiating in a pragmatic way.

- It keeps using itself when it works and abandons itself when it doesn’t.

- With minimal inductive assumptions, performance converges on true expected performance, so picking the lowest-loss method is rational.

- Preferring a method that performs worse is irrational under your own standard of success.

Thus, induction is vindicated by its continued success: it is self-consistent, non-viciously circular, and safe to use.

Leave a comment