◉ A Response to Juan Gonzalez-Ramos

A recent Facebook group post of mine sparked a lengthy and detailed response from Juan Gonzalez-Ramos. Juan touches on everything from evolutionary biology to biblical exegesis to defend the necessity of a “transcendent moral system.” Below is my section-by-section response to his arguments.

The Original Post

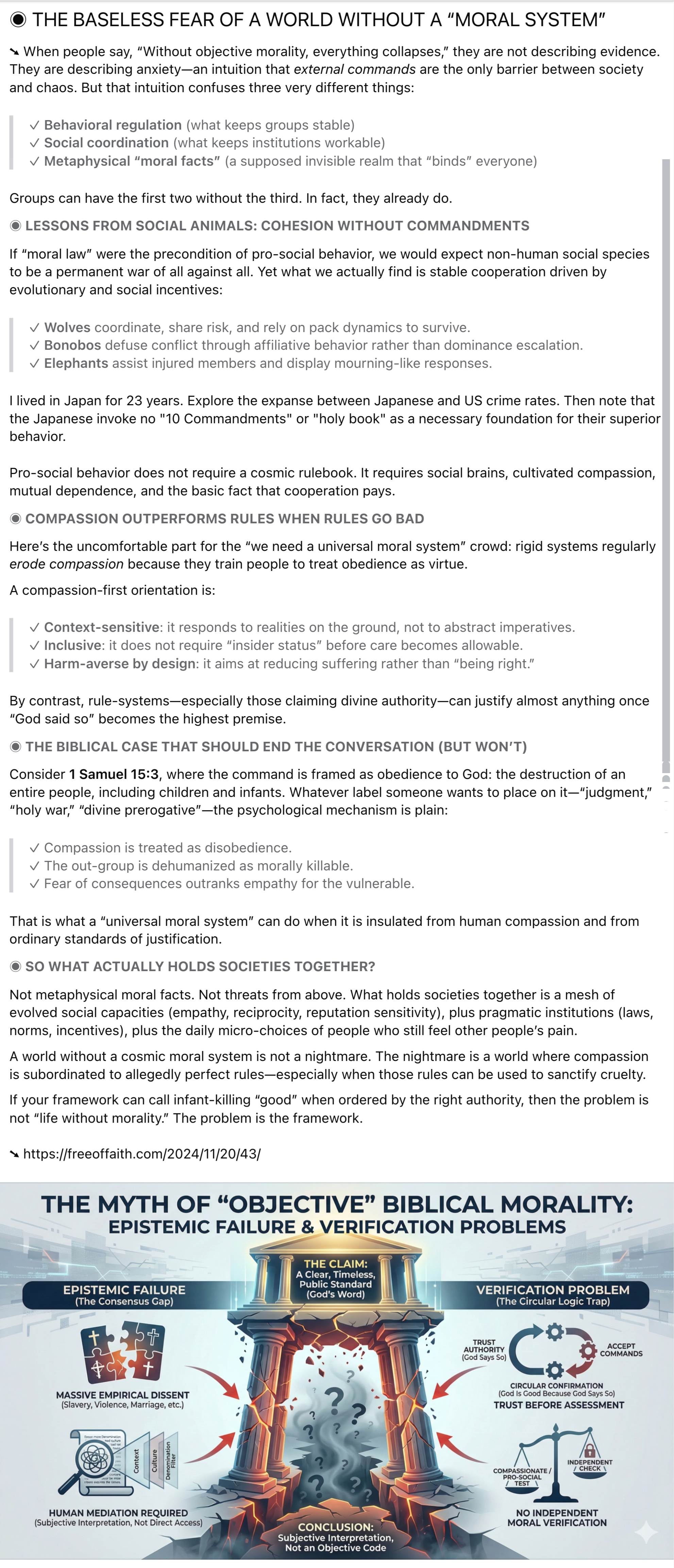

1. The “Oroborus” Fallacy

JUAN SAYS, Let me tell you a story about a conversation I had with a soldier once who swore up and down that discipline wasn’t real because he’d seen wild dogs work together better than some Army units. Made me laugh because he was using disciplined reasoning to argue against discipline existing. You see the problem? Our friend here is doing something similar: making moral arguments about why we shouldn’t need moral arguments. Saying that compassion should trump rules while making rules about when compassion should apply. Declaring what’s truly good while insisting there’s no such thing as true goodness. That’s not philosophy, that’s an Oroborus; the snake eating its own tail.

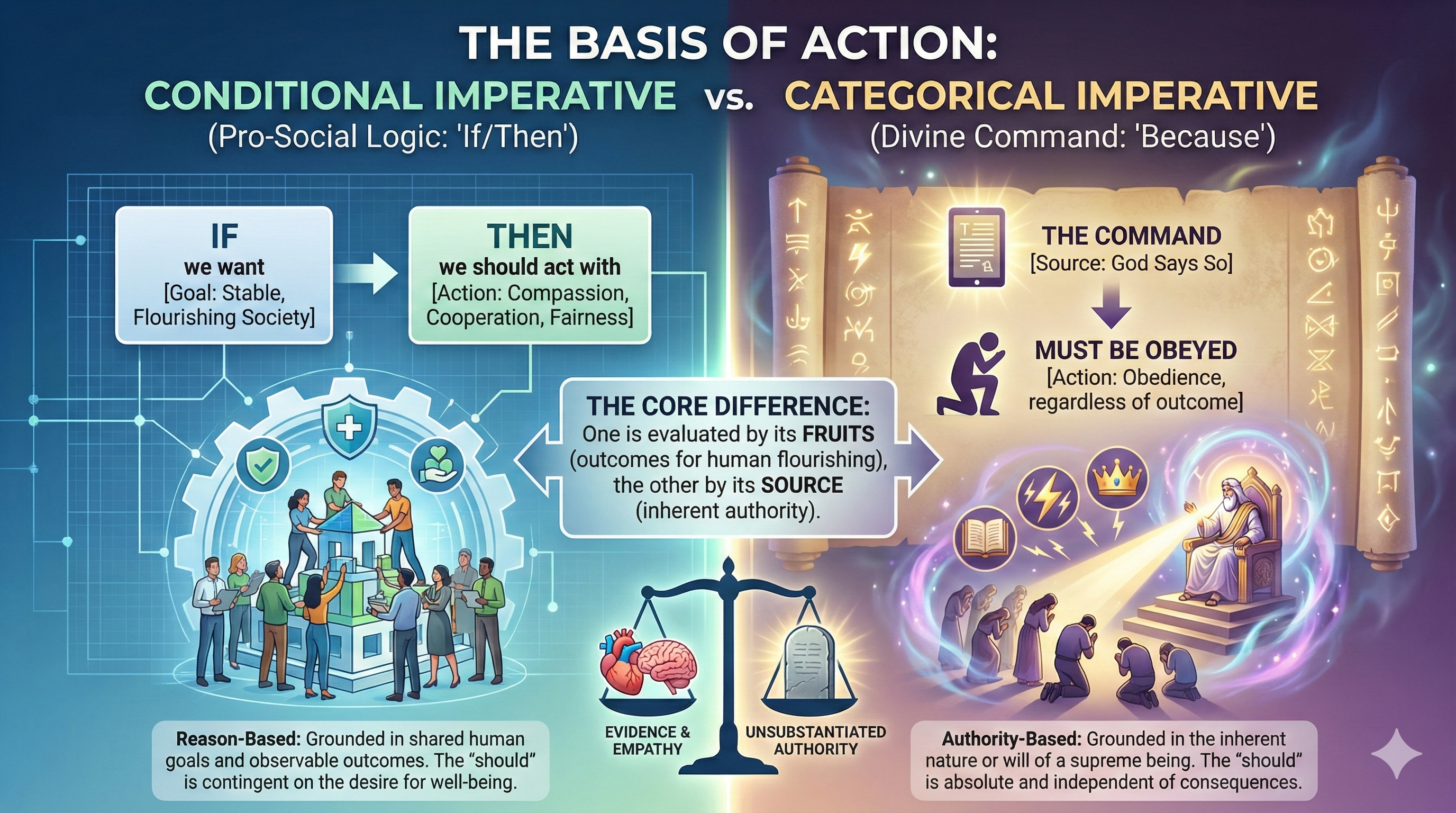

Your “Oroborus” analogy is a clever rhetorical flourish, but it fails because it rests on a fundamental category error. You are conflating descriptive pro-social preferences with prescriptive metaphysical claims.

When I promote compassion or cooperation, I am not “making moral arguments” or “declaring what is truly good” in the sense of appealing to an invisible, universal, or “moral” law. Such claims are entirely unsubstantiated, and I invite you to substantiate the existence of this metaphysical system you claim I am “borrowing” from. In reality, I am simply expressing a preference for certain social outcomes—such as the reduction of suffering—based on my biological nature as a social primate and my cultural conditioning. To suggest that one cannot advocate for pro-social behavior without believing in “moral facts” is like suggesting one cannot prefer the taste of an orange without believing in a “Cosmic Theory of Universal Deliciousness.”

I am not making “rules” about when compassion should apply; I am observing that compassionate behavior generally produces more stable, flourishing environments for beings like us. You claim I am “using disciplined reasoning to argue against discipline,” but the more accurate comparison is that I am using reason to argue against superstition. I am not “eating my own tail”; I am simply pointing out that your “moral” currency has no gold standard behind it—it is an empty assertion.

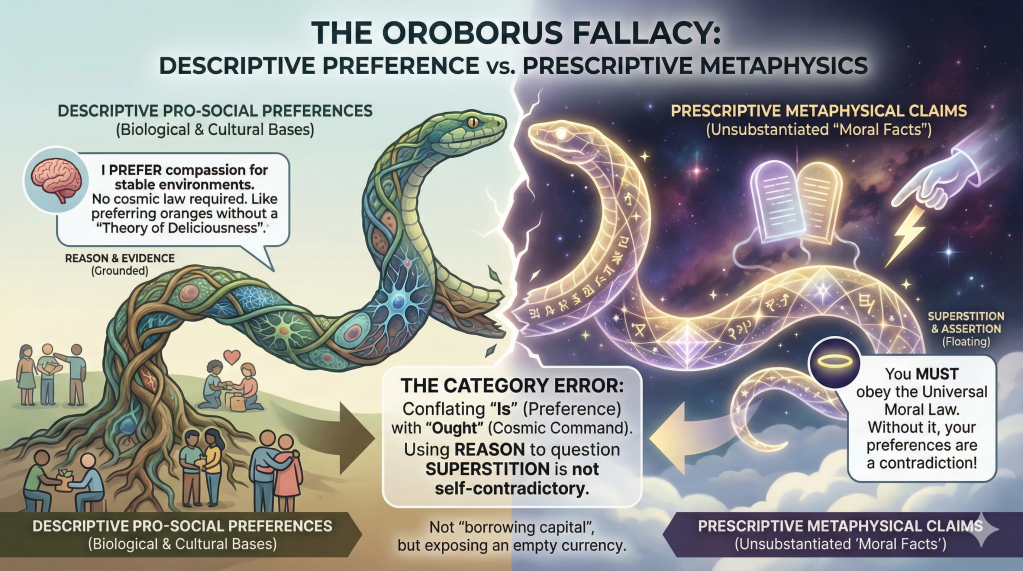

2. The Source of Natural Order

JUAN SAYS, Let’s start with the wolves and bonobos. Beautiful illustration, wrong conclusion. When Scripture says in Romans 2:14-15 that those who don’t have the law “do by nature the things in the law” and show “the work of the law written in their hearts,” it’s not surprising that creatures exhibit pro-social behavior. Of course they do. The question isn’t whether order exists without someone teaching the Ten Commandments. The question is where that order comes from in the first place.

By quoting Romans, you are engaging in a classic case of circular reasoning. You are attempting to use the assertions of your “holy book” to explain the biological data, while simultaneously using that biological data as “evidence” that the book is true.

The “law written on the heart” is a poetic way of describing evolved pro-social instincts, but adding a supernatural author to those instincts is a leap into the dark that remains entirely unsubstantiated. We have a robust, evidence-based explanation for where this order comes from: Natural Selection. Social animals that cooperate, share resources, and minimize internal conflict are more likely to survive and pass on their genes. Cooperation is a survival strategy, not a “moral” imperative.

You ask “where that order comes from,” implying that order requires an Ordainer. This is a teleological assumption that you have yet to justify. In the physical world, we see order emerge from simple rules without a conscious rule-maker—from the formation of snowflakes to the orbit of planets. To claim that pro-social behavior in bonobos or humans is “moral” because a deity “wrote it” is to reify a concept without evidence. I demand that you substantiate this “writer” with something other than the very text that makes the claim.

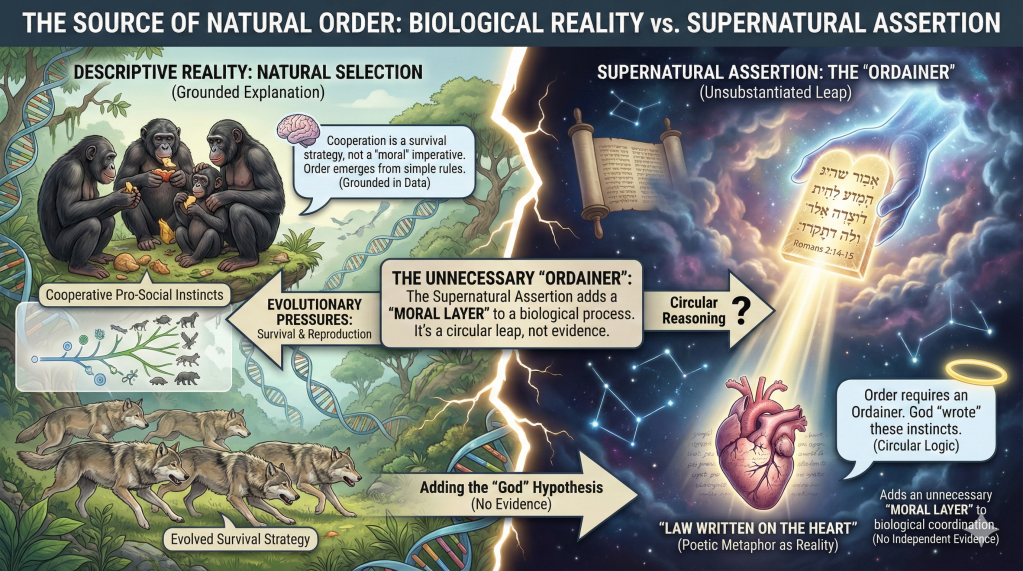

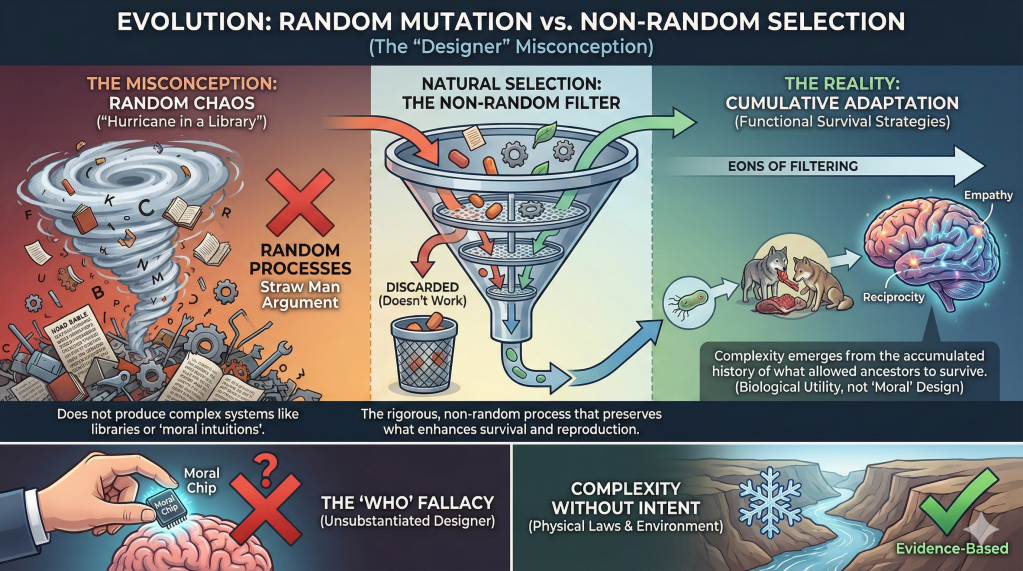

3. Evolution: Filter, Not Random Chaos

JUAN SAYS, Our friend points at pack dynamics and says, “see, no cosmic rulebook needed.” But who wrote the pack dynamics? Who embedded reciprocity into social brains? Who designed the evolutionary pressures that reward cooperation? You can’t escape the question by moving it back one level. If you say “evolution did it,” then you’re just renaming the designer and calling it random. But random processes don’t produce reliable moral intuitions any more than hurricanes produce libraries.

Your argument relies on a fundamental misunderstanding of evolutionary biology and the “hurricanes producing libraries” trope—a classic misdirection. Evolution by natural selection is the opposite of a “random process.” While mutations are random, selection is the ultimate filter. It is a non-random, rigorous process that preserves what works and discards what doesn’t.

Complexity emerges from the interaction of physical laws and environmental constraints. We don’t need a “who” to explain why a river carves a canyon or why water crystals form intricate, symmetrical snowflakes. A library is a collection of static information that requires an external agent to organize it. A biological “intuition” is a dynamic survival mechanism.

Reciprocity isn’t “moral”; it’s functional. In a group setting, individuals who cooperate (reciprocate) out-compete individuals who are purely selfish. Over eons, the “design” is simply the accumulated history of what allowed our ancestors to not die. To call these pro-social impulses “moral intuitions” is to project your own metaphysical desires onto cold, hard biological reality. I demand that you substantiate why a designer is a more parsimonious or evidenced explanation than the self-correcting mechanism of natural selection.

4. The Mechanics of Social Cohesion (The Japan Example)

JUAN SAYS, Now Japan. Twenty-three years there, impressive. Low crime rate is also impressive. But here’s what our friend isn’t asking: why does Japan value harmony over individual expression? Why do they feel shame when they violate social norms? Where did that shame mechanism come from? And most importantly, if morality is just whatever a culture agrees on, then on what grounds do we criticize honor killings in one culture while praising Japanese politeness in another?

Your questions regarding Japan’s social structure are easily answered by sociology, history, and evolutionary psychology without any need for the “moral” scaffolding you are desperate to erect. Shame is a powerful, evolved pro-social regulator. In a group-oriented society, the threat of social exclusion is a survival pressure. Japan has simply cultivated this innate biological capacity into a highly efficient social tool.

You ask on what grounds we can criticize “honor killings” if there is no objective “moral” truth. This is the “relativist boogeyman” argument. I do not need a “transcendent moral fact” to criticize honor killings. I criticize them because they are demonstrably anti-social, cause immense unnecessary suffering, and violate the principle of compassionate reciprocity. We can compare social systems the same way we compare engineering systems. We don’t ask which bridge is “morally right”; we ask which bridge is more stable and better at serving its purpose. A society that values politeness and low crime is preferable to one that practices honor killings because the former promotes flourishing and reduces suffering—outcomes that I, and most humans, happen to prefer. If your only reason for not committing an honor killing is that a book told you it’s “wrong,” then you are the one with the precarious foundation.

5. Functional Comparison vs. Metaphysical Smuggling

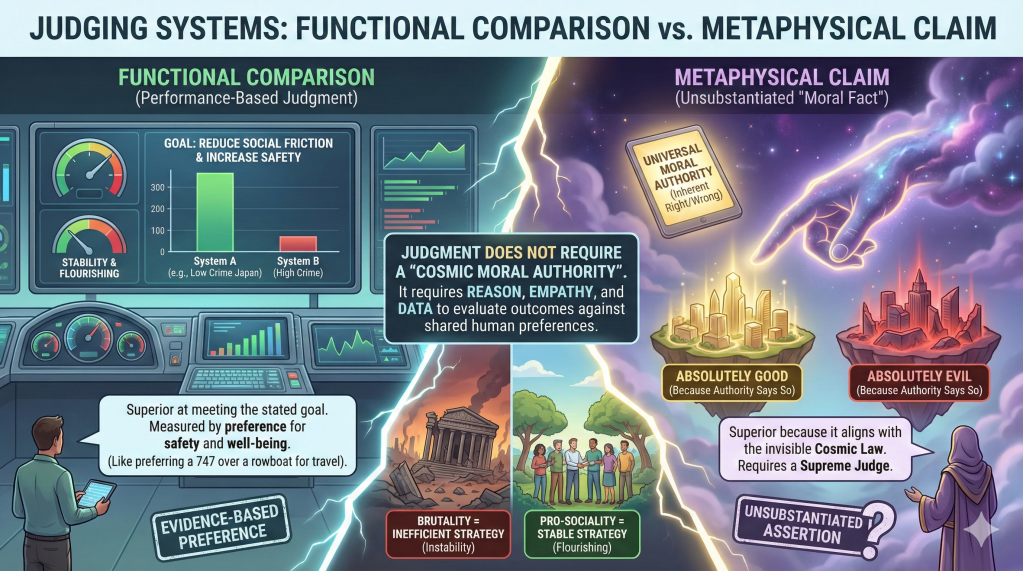

JUAN SAYS, See, the moment our friend says Japanese behavior is “superior,” he has smuggled in an objective standard. Superior, but compared to what? By whose measure? If it’s just evolutionary fitness, then the most brutal empire that survives longest is the most moral. If it’s just social cohesion, then totalitarian conformity beats messy freedom every time. Our friend here wants moral authority to judge between systems without admitting there’s a moral authority above all systems.

You are again mistaking a performance-based judgment for a metaphysical claim. When I say Japanese social behavior is “superior” in the context of crime rates, I am not appealing to a “moral authority above all systems.” I am making a judgment against a specific goal: the reduction of social friction and the promotion of safety.

If we agree that a primary goal of a social contract is to prevent citizens from being robbed or killed, then a system that achieves a lower crime rate is “superior” at meeting that goal. This is no more “moral” smuggling than saying a Boeing 747 is a “superior” machine for crossing the Atlantic than a rowboat.

Furthermore, your claim that “the most brutal empire… is the most moral” is a straw man. Brutality is often an inefficient survival strategy because it invites constant internal rebellion and external coalition-building. Pro-social cooperation, conversely, is a highly stable strategy. I don’t need “moral authority” to judge. I have reason, empathy, and data. I invite you once more: substantiate this “authority above all systems” with something other than your own intuition.

6. Anchoring Mercy and Judgment

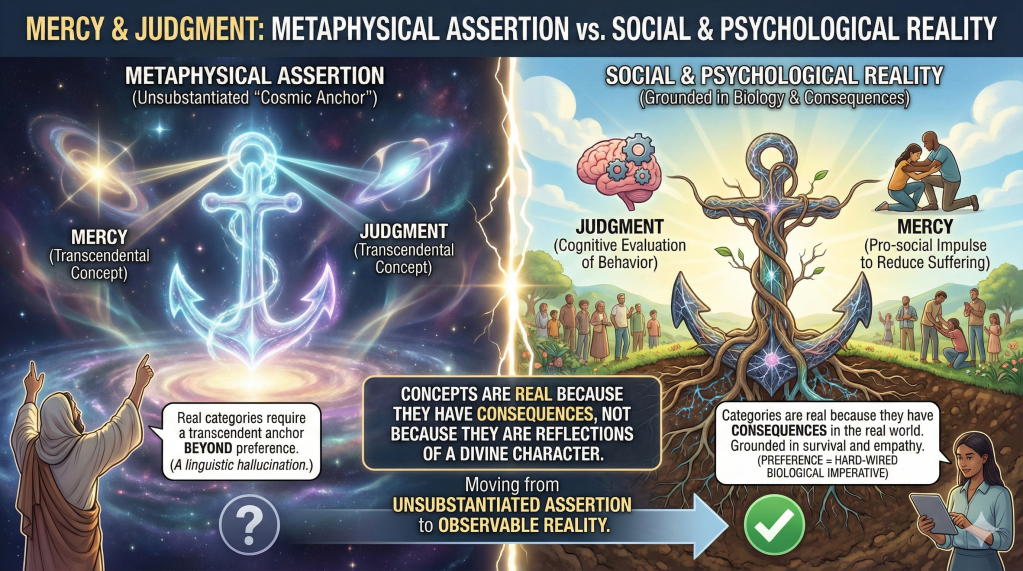

JUAN SAYS, The compassion argument is where it gets really interesting. I agree completely that compassion should inform how we apply principles. James 2:13 says, “mercy triumphs over judgment.” But notice what that verse assumes: both mercy and judgment exist as real categories. You can’t have one triumph over the other if neither one is anchored to anything beyond preference.

Your insistence that categories like “mercy” and “judgment” require a metaphysical anchor is a linguistic hallucination. “Mercy” and “judgment” are perfectly real, but they are social and psychological categories, not metaphysical ones.

Judgment is the cognitive process of evaluating behavior against an expectation. Mercy is the pro-social impulse to suspend a negative consequence in favor of maintaining a relationship or reducing suffering. We can observe these behaviors in primates and in human neurology. They are “anchored” in the very real requirements of group survival and the biological capacity for empathy.

You use the word “preference” as if it were synonymous with “whim.” But human preferences—such as the preference for not being tortured—are hard-wired biological imperatives. I don’t need a “transcendent anchor” to value mercy over judgment; I have the lived reality of a sentient being who understands that a society which prioritizes compassion is more stable and less miserable than one which prioritizes rigid, punitive systems. Your “anchors” are merely unsubstantiated assertions that add zero explanatory power.

7. The Biological Reality of Harm

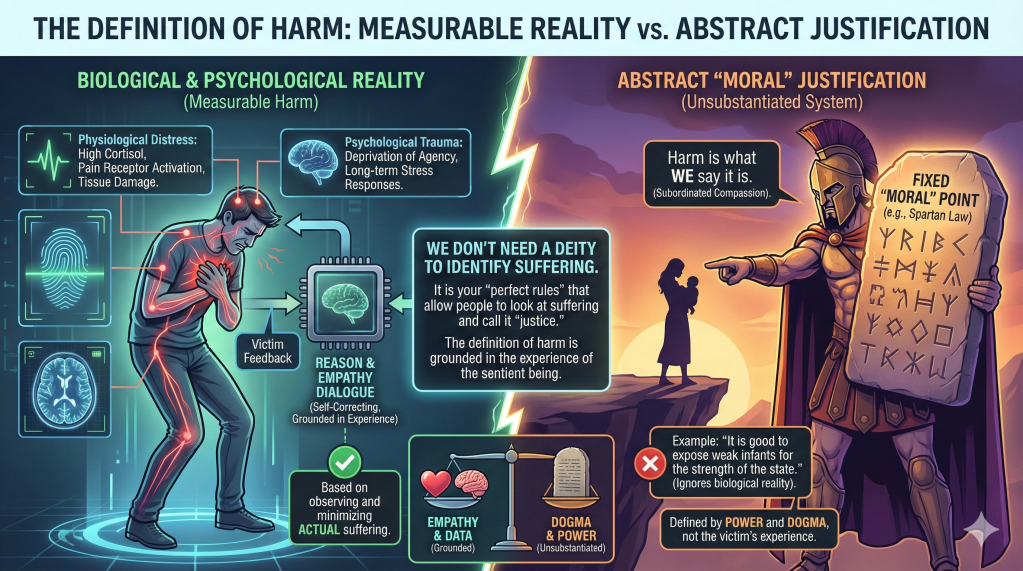

JUAN SAYS, Our friend says compassion is “context-sensitive” and “harm-averse by design.” Fantastic. But whose definition of harm? The Spartans thought it was harmful to let weak infants survive. Some cultures think it’s harmful to let daughters choose their own husbands. Context-sensitivity without a fixed reference point means “whoever has power decides what counts as harm.”

Harm is not an abstract “moral” concept; it is a measurable state of biological or psychological distress. When a Spartan left an infant to die, that infant experienced biological harm—measurable through cortisol levels and pain receptor activation. The fact that the Spartans justified this doesn’t mean they didn’t know what harm was; it means they subordinated compassion to an unsubstantiated “moral” or “ideological” system.

In a compassionate, pro-social framework, the definition of harm is not decided by “whoever has power,” but by the feedback of the victims. We use reason and empathy to negotiate social norms that minimize distress. This isn’t a “fixed point” in the sky; it’s a constant, self-correcting dialogue grounded in the shared experience of being alive.

To suggest we need a deity to tell us that killing infants is harmful is to admit a staggering lack of empathy. It is your “perfect rules” that allow people to look at suffering and call it “justice.”

8. Compassion: A Calculus, Not a Zero-Sum Game

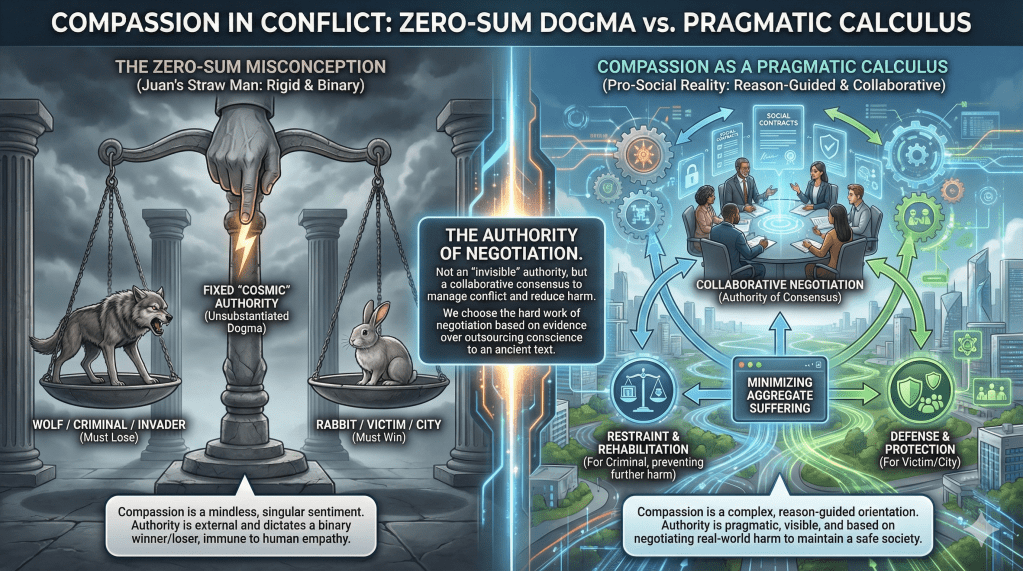

JUAN SAYS, And here’s the real problem with making compassion the highest authority: compassion for whom? When interests conflict, compassion becomes a zero-sum game. You can’t be maximally compassionate to both the wolf and the rabbit. To the criminal and the victim. To the invading army and the city being invaded. Someone has to lose. And whoever decides who loses is exercising authority that their own system says doesn’t exist.

Your “zero-sum game” objection treats compassion as a mindless emotion rather than a reason-guided orientation. A compassion-first orientation does not mean “being nice to everyone”; it means minimizing the total aggregate of suffering.

Compassion for the victim leads to the restraint of the criminal to prevent further harm. Compassion for the inhabitants of a city necessitates defending them against an invading army. These are pragmatic strategies for maintaining a safe society, not “moral facts.”

The “authority” in a pro-social system is collaborative and pragmatic, based on social contracts and the consensus of sentient beings who wish to coexist. It is not an “invisible moral authority”; it is the very visible authority of a community deciding how to best manage conflicts. The real nightmare is your alternative: a “fixed” system where the “authority” can declare that an entire group—even infants—must “lose” because an unsubstantiated dogma supposedly willed it.

9. The Dehumanization Defense (1 Samuel 15:3)

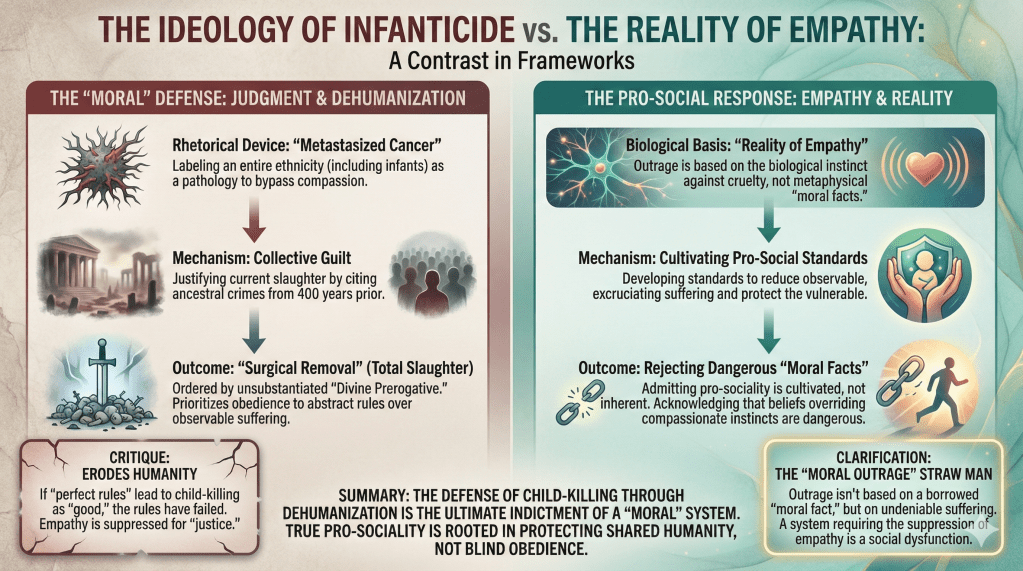

JUAN SAYS, Now let’s talk about 1 Samuel 15:3, because our friend thinks this is the knockout punch. It’s not… Exodus 17:8-16 records that the Amalekites attacked Israel… God gave them four hundred years… It’s the surgical removal of a metastasized cancer after every other treatment failed. But here’s what our friend really misses: he is using his moral outrage at this passage to prove morality doesn’t exist. Think about that. He is basically saying, “this is objectively wrong, therefore there is no objective right and wrong.” That’s philosophically incoherent.

Your defense of 1 Samuel 15:3 is the ultimate indictment of your “moral” system. You are attempting to provide a “rational” justification for the slaughter of infants by labeling an entire ethnicity as a “metastasized cancer.” This is the exact psychological mechanism used by every perpetrator of genocide in human history: dehumanization via collective guilt.

Calling a population of human beings—including nursing infants—a “metastasized cancer” is not a “moral” argument. It is a rhetorical device used to bypass the very compassion you claim to value. If your “perfect rules” lead you to conclude that stabbing an infant to death is a “surgical removal,” then your rules have successfully eroded your humanity.

My outrage isn’t based on a “moral fact” I’ve borrowed from you; it’s based on the biological reality of empathy. I am saying that by any standard of compassion or pro-sociality, the slaughter of infants is an act of extreme cruelty. A world where people believe in “moral facts” that can override their compassionate instincts is far more dangerous than one where we admit that our pro-social standards are something we must cultivate ourselves.

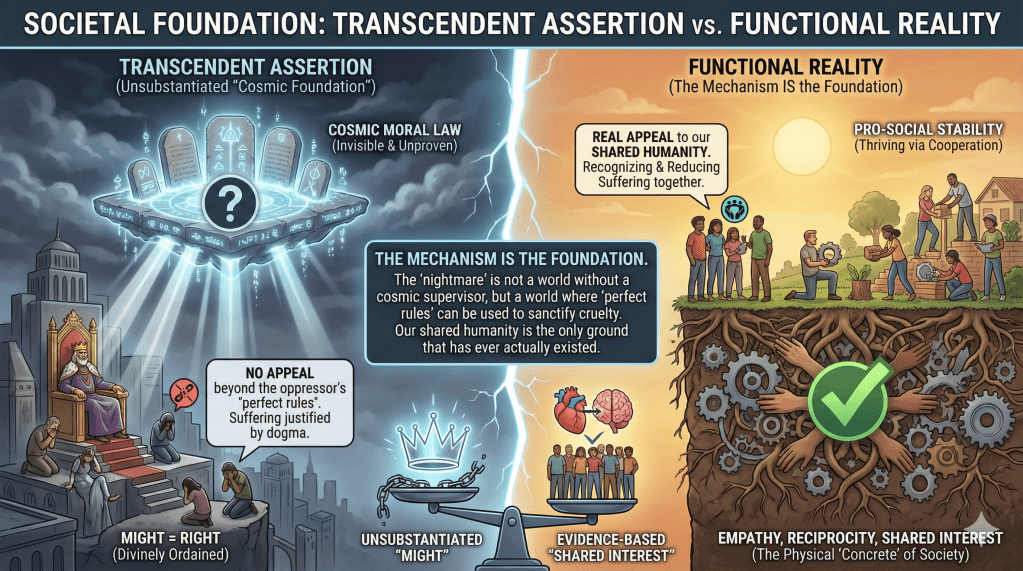

10. The Foundation IS the Mechanism

JUAN SAYS, What actually holds societies together? Our friend says it’s “evolved social capacities plus pragmatic institutions plus daily micro-choices.” But that’s just describing the mechanism, not the foundation… Evolution explains how we got the capacity for moral reasoning. It doesn’t explain why we should use it for good rather than evil… The nightmare isn’t a world with a cosmic moral system. The nightmare is a world where might makes right, where the powerful define good as whatever serves their interests, where victims have no appeal beyond the mercy of their oppressors.

You argue that I am describing the “mechanism” but not the “foundation.” In the real world, the mechanism is the foundation. The “foundation” of a house isn’t a metaphysical concept of “stability”; it is the physical concrete that keeps the structure from sinking. The foundation of society is the very real web of empathy, reciprocity, and shared interest that we have evolved.

We use these capacities for pro-social ends because “good” behavior allows us to thrive, while anti-social behavior leads to systemic breakdown. We choose it because we prefer not to live in a state of perpetual war. You claim that without a cosmic system, “might makes right,” but history shows that transcendent “moral” systems have been the primary tools used to justify the “might” of oppressors by claiming divine ordination.

In a pro-social framework, the appeal for a victim is to our shared humanity and the observable fact of suffering. We don’t need a “transcendent foundation” to stand against oppression; we only need to recognize that the oppressor is causing harm that we ourselves would not wish to endure. I am not “living off borrowed capital.” I am standing on the only ground that has ever actually existed.

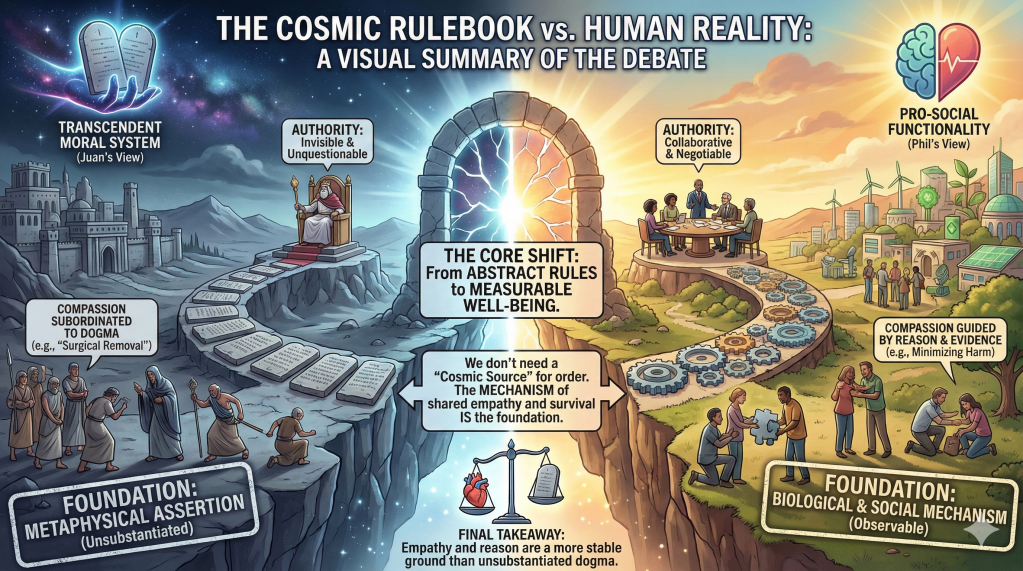

The Takeaway: From Cosmic Shadows to Human Reality

The conversation with Juan highlights a fundamental divide between two ways of seeing the world. One side seeks a “fixed reference point”—an external, metaphysical anchor to justify why we should be kind, why we should cooperate, and what makes a society “good.” The other side, the one I am advocating for, looks at the functional reality of our existence as social animals.

Here is the core of the argument:

- We don’t need a “Source” to have a “Standard”: Order doesn’t require an Ordainer any more than a snowflake requires a jeweler. Pro-social behavior is a successful biological strategy, not a “moral” debt.

- Compassion is a Compass, Not a Rulebook: Unlike rigid systems that can justify the unthinkable (like the “surgical removal” of a population) by appealing to divine authority, a compassion-first orientation remains grounded in the observable reality of suffering.

- The Mechanism is the Foundation: Our shared empathy, our capacity for reciprocity, and our pragmatic social institutions are not “borrowed capital.” They are the concrete reality of human coordination.

The fear that a world without a “cosmic moral system” collapses into a “nightmare of might makes right” is an anxiety, not an evidence-based conclusion. In truth, the real nightmare is any system that allows an abstract idea to override the clear, physical distress of a fellow human being. The innocent Amalekite infants were killed under this “moral” system. And I would have been condemned for trying to save them from their predators.

We don’t need to look to the stars for a reason to be pro-social; we only need to look at each other.

A Formal Demonstration of the failure of Juan’s Position:

- Symbol key (so the later formalizations are unambiguous)

✓ denotes Phil.

✓ denotes Juan.

✓ means

is a moral non-realist (denies objective moral facts).

✓ means action

is objectively wrong (mind-independent).

✓ means agent

has a (possibly strong) preference about

.

✓ means agent

endorses goal

.

✓ means

is better than

relative to goal

.

✓ means

is categorically obligatory.

✓ means

is obligatory conditional on

(a hypothetical imperative).

✓ denotes the act-type “killing Amalekite infants.”

- Blunder 1: Collapsing conditional normativity into categorical obligation

Juan’s move (implicit): treating Phil’s “if you want X, you should do Y” as “you must do Y, full stop.”

Juan’s inference pattern:

✓

✓

Why this is a blunder: the inference is invalid without the extra premise . A conditional obligation does not entail an unconditional obligation.

✓

Concrete countermodel (showing invalidity):

✓ and

can both be true while

is false.

✓

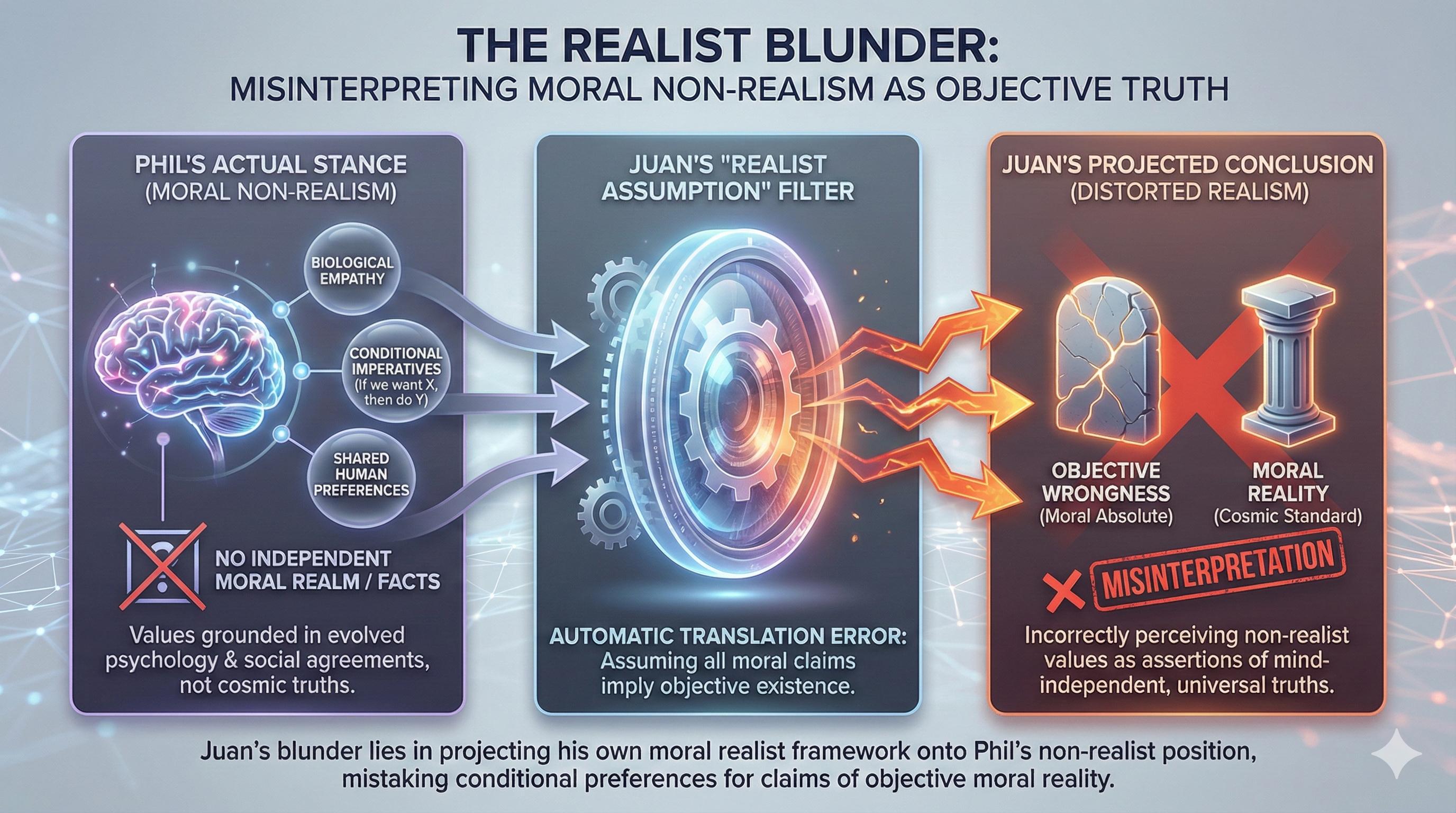

- Blunder 2: Strawman attribution of objective moral claims to an explicit non-realist

Juan asserts (about Phil): “you’re saying it’s objectively wrong.”

But Phil’s stated stance (as quoted by you in-thread) is: there is no moral realm for moral facts to reside in. That commits Phil to denying objective wrongness.

Minimal consistency constraint on Phil’s view:

✓

What Phil can say (and Juan repeatedly treats as forbidden) is preference plus goal-relative evaluation, for example:

✓

✓

Juan’s strawman leap is:

✓

That implication does not follow.

✓

- Blunder 3: Equivocation on evaluative language (treating “better/superior” as automatically “morally objective”)

Juan’s assumed bridge principle:

✓

This is a category mistake: “better relative to a specified goal” is not the same kind of claim as “objectively wrong.” Goal-relative comparisons are compatible with non-realism; objective wrongness is not.

The minimal separation Juan ignores:

✓

- Blunder 4: Treating goal pluralism as if it destroys all goal-relative assessment

Juan’s stated thought: societies can have competing goals, so evaluation is illegitimate.

His implied argument:

✓

Even ignoring the subscripts, the structure is invalid. The existence of multiple goals does not entail that no goal-relative evaluation is possible. At most, it blocks a single, universal ranking across all goals.

Correct logical form (what actually follows):

✓

- Blunder 5: “Psychopaths lack empathy, therefore you cannot restrain them without objective morality”

Juan’s implicit inference:

✓

This is a non sequitur. Restraint can be justified instrumentally (self-defense, deterrence, coordination stability) without invoking objective moral facts.

A simple refutation schema:

✓

✓

Juan assumes a hidden premise that all justification must be of the objective-moral kind. That premise is precisely what is under dispute.

- Blunder 6: The “obligation requires authority; authority requires God” chain smuggles its conclusion

Juan’s core chain (as he uses it):

✓

✓

✓

Where the blunder sits: the second premise effectively defines all genuine authority as divine, which is the conclusion’s substance, not an independently supported premise.

You can expose the circularity by noting the definitional substitution:

✓

Once inserted, the “argument” is just a re-labeling exercise.

- Blunder 7: “Without objective morality, condemnation reduces to mere preference, so Nazis are not wrong”

Juan’s false dilemma structure:

✓

✓

✓

The disjunction is incomplete. There are intermediate normative frameworks that are neither objective-moral facts nor “mere whim,” including goal-relative rationality, contractualism, coordination equilibria, and institutional constraint systems.

Formally, he assumes:

✓

But a more accurate partition is:

✓

Juan’s conclusion does not follow without excluding these additional live options.

- Blunder 8: The “you’re borrowing from theism” move is an underdetermined inference (and often a genetic fallacy)

Juan’s claim pattern:

✓

Even if we grant:

✓

the conclusion does not follow, because there are multiple competing explanations for the same datum.

Underdetermination can be stated as:

✓

Here is “people have strong evaluative intuitions,”

is theism, and

is any naturalistic genealogy of norms (evolutionary, cultural, game-theoretic, developmental).

- Blunder 9: Self-contradictory interpretation of Phil’s semantics after Phil explicitly corrects him

Juan persists in attributing to Phil the claim:

✓

while Phil explicitly asserts . If Juan accepts Phil’s self-description as a premise (which he claims to), then Juan cannot coherently keep asserting that Phil is making objective-moral claims without adding an argument that Phil’s self-description is false.

The inconsistency can be pinned as:

✓

This set is inconsistent unless Juan supplies a defeater for the middle conditional or rejects .

- Blunder 10: Scripture-citation as a premise in a dispute about whether Scripture has authority

Juan repeatedly uses:

✓

But that is exactly the authority principle under contention. In a debate with a non-believer, the rule is not neutral; it is a partisan inference rule.

Its non-neutrality is visible as:

✓

So Juan’s “proof” steps do not transmit warrant to Phil, because they rely on an inference rule Phil does not grant.

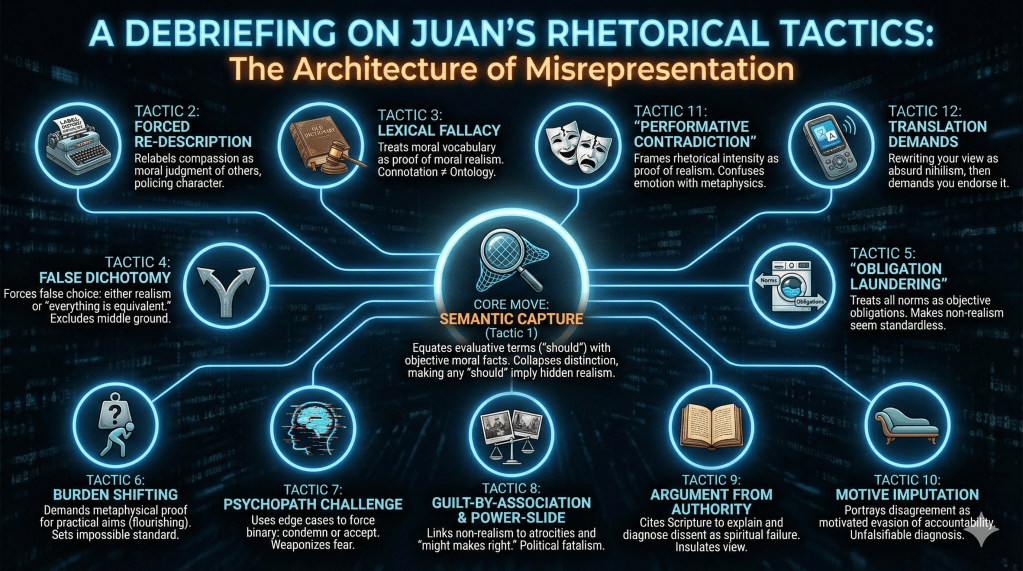

A Debriefing on Juan’s Attempt to Misrepresent My Position:

◉ Symbol key

✓ = you (Phil).

✓ = Juan.

✓ = you deny objective moral facts.

✓ =

is a moral fact claim (mind-independent).

✓ =

is an evaluative claim (goal-relative, preference-relative, or functional).

✓ = categorical obligation.

✓ = conditional obligation given goal

.

◉ Tactic 1: Semantic capture (treating ordinary evaluative language as proof of objective moral commitments)

You keep using evaluative language—”superior,” “better,” “should”—while denying the existence of any transcendent reference point to anchor those evaluations.

✓ What he is doing: He tries to collapse the distinction between (a) goal-relative evaluation and (b) objective moral fact claims. If he can make that collapse stick, any use of “should,” “better,” or “superior” becomes evidence that you secretly affirm objective moral standards.

✓ The underlying maneuver:

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: Many readers have a default linguistic intuition that “should” is always “moral should.” He exploits that ambiguity.

✓ What makes it weak: In ordinary reasoning, people constantly use functional “should” (engineering, medicine, athletics, policy) without implying objective moral facts. The correct bridge is not automatic; it depends on whether the “should” is conditional on an explicit goal.

✓

✓

◉ Tactic 2: Forced re-description (relabeling your compassion talk as a claim that dissenters are morally defective)

That’s not a preference, Phil. That’s a moral claim. You’re declaring it wrong, not just personally distasteful. You’re saying anyone who doesn’t share your preference is morally deficient.

✓ What he is doing: He upgrades your condemnation of an act into a condemnation of persons, then reads that as “objective” and “binding.” This is a re-description tactic: he tells the audience what you “are really saying,” regardless of your explicit meta-ethical framing.

✓ The hidden steps:

✓

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: It portrays your stance as covertly policing people’s character, which primes the “you’re smuggling morality” accusation.

✓ What makes it weak: Even if you strongly condemn an act as “cruel,” it does not follow that you are asserting objective wrongness, and it does not follow that you are asserting a universal defect in all dissenters. Those are add-on premises he supplies.

◉ Tactic 3: Lexical fallacy (arguing from the connotations of words to the ontology you must accept)

You called the Amalekite command “the ultimate indictment” of my moral system. Indictment is a legal and moral term implying guilt and wrongdoing. If there are no moral facts, there’s no indictment, just different preferences.

You wrote that my framework “has successfully eroded your humanity.” Erosion implies degradation from a better state to a worse one. That’s a value judgment requiring a standard.

✓ What he is doing: He treats word-choice as a metaphysical confession. If a term often appears in moral or legal contexts, he argues that using the term commits you to moral realism.

✓ The underlying inference pattern:

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: It feels like “language forensics.” It invites the audience to think your vocabulary is a leak of your “real beliefs.”

✓ What makes it weak: People routinely borrow moralized vocabulary for rhetorical force, social critique, or goal-relative evaluation without endorsing objective moral facts. Word connotation does not entail ontology.

✓

◉ Tactic 4: False dichotomy (either moral realism, or “everything is morally equivalent”)

Are you a consistent moral non-realist who admits the Amalekite command, the Holocaust, and helping old ladies cross the street are all morally equivalent, just representing different biological preferences? Or are you actually operating with moral intuitions you can’t account for in your system?

✓ What he is doing: He frames your position as having only two options: accept objective moral facts, or accept a caricatured nihilism where all acts are “equivalent.”

✓ The forced-choice structure:

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: It makes your view look psychologically and socially unlivable, then pressures you to retreat to his framework.

✓ What makes it weak: Non-realism does not entail practical indifference or evaluative equivalence. One can deny objective moral facts while still having strong preferences, policy commitments, and goal-relative rankings (harm reduction, social stability, compassion-as-a-value, etc.). His dichotomy excludes the middle ground by fiat.

◉ Tactic 5: “Obligation laundering” (treating any normative pressure as objective obligation)

Why does measurable distress create an obligation for me to care?

But “should” is a moral category. Where does that obligation come from if not from something beyond biology?

✓ What he is doing: He insists that unless you can produce categorical obligation, you cannot justify any norm-guidance at all. Then he treats that gap as proof you are secretly relying on objective obligation.

✓ The move: replace motivations, commitments, and conditional norms with .

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: It makes your framework look like it cannot tell anyone to do anything, which sounds like “no standards.”

✓ What makes it weak: Many “should” claims are conditional on aims and constraints (health, cooperation, stability, predictability). Those can have real force without being categorical obligations.

✓ can guide action without implying

.

◉ Tactic 6: Burden shifting (demanding you justify why anyone should want stability, flourishing, reduced suffering)

You say “if we wish to live in a stable, flourishing society” as if that’s a given. But that’s the whole question. Why should anyone wish that?

✓ What he is doing: He treats widely shared human aims as needing metaphysical grounding, then treats any inability to deliver “objective” grounding as defeat.

✓ The burden-shift form:

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: It makes your view seem arbitrary: “just vibes.”

✓ What makes it weak: This is an inflated standard. In practice, many axioms and aims are taken as practical starting points (health over illness, safety over predation, coordination over breakdown). A meta-ethical position can be non-realist while still treating those aims as deeply entrenched features of human psychology and social viability.

◉ Tactic 7: Psychopath challenge (using edge cases to force you into moral realism)

Psychopaths have defective mirror neuron systems. Are they wrong to lack empathy, or just different? If just different, you have no grounds to restrain them. If wrong, you’re admitting a standard beyond biology.

✓ What he is doing: He uses a hard case to force a binary: either (a) you say psychopaths are “wrong” (which he labels moral realism) or (b) you lose any basis for restraint.

✓ The trap structure:

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: It weaponizes a scary counterexample to make non-realism look socially disabling.

✓ What makes it weak: Restraint can be justified instrumentally (risk reduction, self-defense, institutional stability) without invoking objective moral facts. The inference “no moral realism, therefore no restraint” is not valid.

◉ Tactic 8: Guilt-by-association and power-slide (from “no objective morality” to “Nazis were not wrong” to “might makes right”)

The Nazis had power. The Stalinists had power. On what grounds do you condemn them if morality is just evolved preference?

In practice, it’s whoever has more power. That’s the inevitable result of your system.

✓ What he is doing: He slides from meta-ethical non-realism to political fatalism: if there is no objective moral law, then outcomes are determined only by force, and condemnation is incoherent.

✓ The slide:

✓

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: It makes your view feel complicit with atrocities by implying you cannot say “wrong” in a meaningful way.

✓ What makes it weak: Condemnation can be grounded in goals, harms, rights-as-institutions, mutual constraints, and coordination norms without positing objective moral facts. Also, “power decides in practice” is a sociological claim; it does not follow from non-realism as a thesis about moral facts.

◉ Tactic 9: Argument from authority (Scripture as explanation, diagnosis, and closure)

Scripture explains this perfectly.

Romans 2:14-15 says even those without the law “show the work of the law written on their hearts.”

Romans 1:18 says people “suppress the truth in unrighteousness.”

✓ What he is doing: He uses Scripture to (a) explain your psychology, (b) label your disagreement as suppression, and (c) present his conclusion as already settled.

✓ The structure (as an inference rule):

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: It shifts the debate from shared premises to in-group authority, then portrays dissent as moral and spiritual failure rather than a live philosophical dispute.

✓ What makes it weak in your dialectical context: The inference rule is not neutral. If the authority of Scripture is precisely what is contested, it cannot function as a premises-to-conclusion bridge for your side.

◉ Tactic 10: Motive imputation (portraying your position as evasion of accountability)

Acknowledging the Lawgiver means acknowledging you’re accountable to Him.

That’s the real issue, Phil.

✓ What he is doing: He moves from argument to diagnosis: disagreement is not framed as a rational difference but as motivated resistance.

✓ The implied claim:

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: It insulates his view from rebuttal. Any counterargument becomes further “evidence” of suppression.

✓ What makes it weak: It is largely unfalsifiable within the exchange and functions as a conversational trump card. It also reverses burdens: instead of defending his premises, he pathologizes your rejection of them.

◉ Tactic 11: “Performative contradiction” framing (you cannot talk this way unless moral facts exist)

Your entire blog post drips with moral condemnation that only makes sense if moral facts exist.

Your language reveals the truth.

✓ What he is doing: He treats your rhetorical intensity as a proof that your meta-ethic is false: if you speak as if something matters, then objective moral facts must exist.

✓ The core move:

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: It plays on the intuitive thought that “seriousness requires objectivity.”

✓ What makes it weak: Emotional force and practical seriousness can attach to values, commitments, and social aims without implying mind-independent moral facts. The inference confuses psychological weight with metaphysical status.

◉ Tactic 12: Tightening the noose with “translation demands” (he rewrites your view into a cruder form, then demands you endorse it)

Either defend consistent moral non-realism (which means admitting nothing is actually wrong, just differently preferred), or acknowledge that your moral intuitions point to something beyond biology.

✓ What he is doing: He stipulates what “consistent non-realism means,” then forces you to accept his stipulated translation. If you reject it, he treats that as concession.

✓ The stipulation:

✓

✓ Why it works rhetorically: It frames you as afraid to own the consequences of your view.

✓ What makes it weak: It is not an agreed definition; it is an argumentative redefinition designed to make non-realism sound absurd and socially corrosive.

Juan’s core move is semantic capture: he treats your evaluative language (“should,” “better,” “cruelty,” “indictment,” “eroded humanity”) as if it automatically entails objective moral facts, formalized as . From there he runs a set of reinforcing tactics: he forces a false dichotomy in which

supposedly implies “everything is equivalent,” he launders conditional norms into categorical obligations by sliding from

to

, and he uses edge cases (psychopaths) plus atrocity comparisons (Nazis, Stalin) to claim you cannot coherently condemn or restrain anyone without moral realism. He then shifts burdens by demanding metaphysical justification for common human aims, and closes the loop by citing Scripture as both an authority and a psychological diagnosis (“suppression,” “accountability”), which insulates his position from rebuttal by treating disagreement as motive rather than argument.

A few days later, Juan’s still at it on another post.

Phil Stilwell (Original Post)

◉ ◉ ◉ Does the felt absurdity of a universe with no ultimate justice make a God of ultimate justice necessary?

A common apologetic impulse runs like this:

“If there’s no ultimate justice, reality is intolerable (or ‘absurd’). Therefore, there must be a God who guarantees ultimate justice.”

This post challenges that inference. Not by denying that humans strongly want justice, but by asking whether that want can function as evidence.

◉ 1) Desire is not evidence We experience “this shouldn’t be” constantly, but that does not imply “therefore a cosmic fixer exists.”

✓ Wanting justice does not establish that reality contains ultimate justice. ✓ Psychological need does not equal metaphysical fact. ✓ Feeling “it must balance out in the end” is not the same as showing it does.

If the argument is “I can’t accept a reality without ultimate justice,” then the engine of the inference is emotional necessity, not evidential necessity.

◉ 2) “Absurd” usually means “I hate this,” not “it’s incoherent” A universe where heinous acts sometimes go unpunished and sacrifices go unrewarded is not logically contradictory. It is simply a universe that does not align with our preferences. Calling that “absurd” is typically an emotional protest, not a logical diagnosis.

◉ 3) Analogies that expose the leap ✓ Unrequited love: deep longing does not create entitlement. Pain is real; it doesn’t prove a cosmic debt exists. ✓ Storm and sailor: a storm is indifferent. Wanting a hand on the tiller doesn’t prove one exists. ✓ Scales without weights: insisting the cosmos must balance perfectly often adds assumptions purely to soothe discomfort.

◉ 4) The “God guarantees justice” move inherits major liabilities ✓ Circularity risk: “Ultimate justice must exist, therefore God exists” assumes what it needs to prove. ✓ Proportionality tensions: many Christian models of final judgment involve infinite consequences for finite lives. You can defend that theologically, but you cannot treat it as automatically coherent with ordinary proportional consequences. ✓ Unnecessary hypothesis: indifferent natural laws already explain why ultimate justice is not guaranteed. Adding a cosmic judge is an extra metaphysical layer that requires independent support.

◉ 5) Questions for Christian respondents ✓ What evidence (not emotional necessity) moves you from “I want ultimate justice” to “ultimate justice exists,” and from there to “the Christian God guarantees it”? ✓ If your answer is “God’s justice is higher than ours,” how do you keep “justice” from collapsing into “whatever God does,” which explains nothing?

◉ Closing challenge A universe without ultimate justice may be emotionally difficult. But difficulty is not evidence. If you think ultimate justice is real, make the case with argument and support—not with the psychological weight of wishing it were so.

Juan Gonzalez-Ramos

Phil, I’m genuinely impressed. You’ve managed to write an entire post about how ultimate justice doesn’t exist while simultaneously presupposing that it should. That takes a special kind of philosophical gymnastics. (1/2)

1. The Performative Contradiction Strikes Again You write that calling a universe without ultimate justice “absurd” is just emotional protest, not logical diagnosis. You insist that such a universe isn’t logically contradictory, just misaligned with our preferences. And then, without apparently noticing the irony, you spent thousands of words on your blog condemning the Amalekite command as “the ultimate indictment” of my moral system. So which is it, Phil? Is condemning injustice just an emotional protest, or is it recognizing genuine moral deficiency? Because you can’t have it both ways. Either your outrage about 1 Samuel 15:3 was just you expressing personal discomfort (in which case, who cares?), or you were making a claim about objective wrongness (in which case, welcome to moral realism). When you call the Amalekite judgment “extreme cruelty” and compare my defense to “genocidal thinking,” you’re not just saying “I personally prefer different outcomes.” You’re saying something is genuinely, objectively wrong with a system that would allow such things. That’s an appeal to ultimate justice whether you admit it or not.

2. Desire as Evidence When It’s Universal and Properly Basic Your first point claims desire isn’t evidence. Well, that depends entirely on what kind of desire we’re talking about. If I desire a cheeseburger, that’s not evidence cheeseburgers exist in general—though it’s pretty good evidence I’m hungry. But if every human who has ever lived desires justice, if that desire transcends culture and history and individual preference, if it functions as a properly basic belief that shapes how we understand reality, then yes, that’s evidence we’re tracking something real. C.S. Lewis made this point brilliantly, though I know you’ll dismiss him because he’s a Christian apologist. But the logic stands regardless of the source. We don’t find desires in nature for which no satisfaction exists. Every natural appetite corresponds to a real object: hunger to food, thirst to water, sexual desire to reproduction, curiosity to knowledge. The universal human hunger for ultimate justice suggests justice itself is real, not that we’re all experiencing a cosmic delusion. Your rebuttal would be that this is “just evolution.” But evolution explains why we have the capacity for desiring justice. It doesn’t explain why that desire points to something real rather than being merely adaptive but ultimately illusory. You keep confusing mechanism with meaning.

3. “Absurd” Means Exactly What I Think It Means You claim “absurd” is just emotional language meaning “I hate this.” But that’s a convenient reduction that misses what philosophers actually mean by absurdity. When Camus talked about the absurd, he wasn’t just whining about his preferences. He was identifying a fundamental disconnect between human consciousness demanding meaning and a universe that supposedly provides none. A universe where heinous acts go unpunished and sacrifices go unrewarded isn’t just “not aligned with our preferences.” It’s a universe where our deepest moral intuitions systematically mislead us about the nature of reality. It’s a universe where we can’t trust our most basic cognitive faculties when it comes to moral truth. That’s not just unfortunate. It’s absurd in the philosophical sense: it renders our moral reasoning fundamentally unreliable. But here’s the delicious irony: you don’t actually believe that. Your entire blog demonstrates you trust your moral reasoning implicitly. You think you can reliably identify injustice, condemn cruelty, recognize compassion as valuable. You just won’t admit where that reliability comes from.

4. Your Analogies Prove My Point Your unrequited love analogy is supposed to show that longing doesn’t create entitlement. Agreed. But notice what you’ve done: you’ve compared the universal human desire for justice to one person’s particular romantic longing. That’s not parallel at all. A better analogy would be: every human who has ever lived experiences romantic longing, consistently points toward romantic fulfillment as genuinely good, and can’t function socially without the concept that some romantic arrangements are better than others. In that case, yes, the universal pattern would be evidence that romance corresponds to something real in human nature and social reality. Your storm and sailor analogy is even worse. Yes, storms are indifferent. But humans aren’t storms, and moral reality isn’t weather. The question isn’t whether nature is indifferent (it obviously is). The question is whether the moral law we all experience has a foundation. Pointing at indifferent natural processes doesn’t address that question at all. (continues…)

Juan Gonzalez-Ramos (Continuation)

Phil, (2/2)

5. The “Unnecessary Hypothesis” Gambit You claim adding God as cosmic judge is an “unnecessary hypothesis” because indifferent natural laws already explain why ultimate justice isn’t guaranteed. But this completely misses the point of the argument. Nobody’s claiming we need God to explain why bad things happen. We’re claiming we need God to explain why we’re justified in calling them bad. Natural laws explain events. They don’t explain values. They don’t explain why we should care about justice rather than merely noting that we do care. Here’s where your position becomes incoherent. You want to say:

- There is no ultimate justice

- But we should still care about justice

- And people who don’t care about justice are genuinely deficient

- Though that deficiency isn’t real, just our preference

- But we’re right to act on that preference as if it creates obligations

- Even though obligations don’t actually exist

That’s not a coherent position, Phil. That’s philosophical whack-a-mole. Every time I point out that you’re making objective moral claims, you retreat to “just preferences.” Every time I point out that preferences don’t create obligations, you start using language that presupposes objective obligations exist.

6. Addressing Your “Questions for Christian Respondents” You ask what evidence moves us from “I want ultimate justice” to “ultimate justice exists.” Here’s the actual argument, which you keep misrepresenting:

- All humans across all cultures recognize certain things as genuinely right or wrong

- This recognition isn’t just preference because we treat it as binding even on those who don’t share it

- Moral obligations that bind regardless of preference require a foundation beyond mere consensus or evolution

- That foundation must have the properties of transcendence (applying universally), authority (creating genuine obligation), and moral perfection (knowing the right standard)

- Only God possesses those properties

- Therefore, moral obligations point to God’s existence

Notice that’s not “I want justice, therefore God.” It’s “universal moral knowledge requires explanation, and God is the only adequate explanation.” Your “unnecessary hypothesis” claim only works if you can explain moral normativity without God. You can’t. You keep trying to reduce “ought” to “is” and failing. You ask if “God’s justice is higher than ours” makes justice collapse into “whatever God does.” No, because God’s nature is the standard. God doesn’t decide arbitrarily what’s just. Justice flows from His character. When Scripture says in Deuteronomy 32:4 that “He is the Rock, His work is perfect; for all His ways are justice,” it’s not saying God’s choices define justice. It’s saying God’s actions perfectly express the justice that is intrinsic to His nature. This isn’t circular. It’s recognizing that ultimate standards must be grounded in ultimate reality. Either moral truth is grounded in God’s nature, or it’s grounded in nothing (your position), or it’s grounded in some abstract realm independent of God (Platonic forms, which creates other problems). The theistic option is the only one that accounts for moral truth being both objective and normative.

The Real Closing Challenge You write that emotional difficulty isn’t evidence and we should make our case with argument and support. I’ve been doing exactly that. But you keep dodging. You’ve spent this entire exchange:

- Making moral claims while denying moral facts exist

- Using condemnatory language while insisting you’re just expressing preferences

- Appealing to justice, compassion, and harm reduction while denying these concepts have objective content

- Demanding I prove God exists while refusing to account for the moral knowledge you constantly demonstrate

Here’s my challenge back to you, Phil. Stop hiding behind formal notation and meta-ethical labels. Answer one simple question directly: When you wrote that the Amalekite command is “by any standard of compassion or pro-sociality, an act of extreme cruelty,” were you making an objective moral claim or just expressing personal preference? If objective claim: Welcome to moral realism. Now you need to account for where objective moral truth comes from. If personal preference: Then why should anyone care what you prefer? Why spend thousands of words arguing about it? Why use language like “ultimate indictment” and “eroded humanity” when you could just say “not my cup of tea”? You can’t answer that question honestly without either admitting moral realism or revealing that your condemnation of biblical texts was nothing but emotional venting dressed up as philosophical argument.

The Absurdity You Won’t Acknowledge The real absurdity here isn’t that the universe lacks ultimate justice. The real absurdity is your position: that we should care deeply about justice while admitting justice is just a preference, that we should condemn atrocities while denying anything is genuinely wrong, that we should trust our moral reasoning while believing it evolved as an adaptive illusion. You’re like a man who insists he doesn’t believe in mathematics while using mathematical reasoning to prove his point. Every argument you make presupposes the very thing you’re denying. Romans 1:21-22 describes this perfectly: “Although they knew God, they did not glorify Him as God, nor were thankful, but became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Professing to be wise, they became fools.” You have the moral knowledge. You demonstrate it constantly. You just refuse to acknowledge the source because that would mean accountability. That’s not intellectual sophistication, Phil. That’s suppression of truth in unrighteousness, exactly as Scripture predicts. So here’s my closing challenge: Either live consistently with moral non-realism (which means accepting that condemning genocide is no more objectively true than preferring vanilla ice cream), or acknowledge that your moral intuitions point to moral reality that your naturalistic worldview can’t account for. The absurdity isn’t that reality might lack ultimate justice. The absurdity is you pretending you don’t believe in ultimate justice while spending thousands of words demanding it.

Phil Stilwell

Juan Gonzalez-Ramos You are again telling me what I believe. That won’t cut it here. Honest engagement, at minimum, requires the humility to actually ask what your interlocutor believes rather than telling him what he believes. Rereading 1 Peter 3:15 will also do you good.

Juan Gonzalez-Ramos

Phil, I appreciate the irony here more than you might realize. You’re expressing moral outrage that I’ve failed to engage with you properly. You’re claiming I’ve violated standards of “honest engagement” and need more “humility.” You’re suggesting my behavior is deficient according to the principles in 1 Peter 3:15. But here’s the problem: on your stated philosophy, none of those claims have any force. If moral non-realism is true, then “honest engagement” is just your preference, “humility” is just a trait you happen to value, and scriptural standards are just ancient cultural preferences with no binding authority. Your offense only makes sense if I’ve violated something objective, something real, something that creates genuine obligations. So which is it? Am I actually wrong to characterize your position the way I have, or do you just prefer I didn’t? Because if it’s the latter, why should I care about your preferences any more than you care about mine?

Now let me address your specific objection. You claim I’m telling you what you believe rather than asking. But that’s not quite accurate. I’ve been pointing out the contradiction between what you SAY you believe and what your LANGUAGE reveals you actually believe. That’s not the same thing. You say you’re a moral non-realist. I’m taking you at your word about that self-identification. But then you write things like “the ultimate indictment,” “eroded humanity,” and “extreme cruelty” when discussing moral issues. That language only makes sense if moral facts exist. So I’m not telling you what you believe. I’m pointing out that your stated beliefs and your demonstrated beliefs contradict each other. This is called a performative contradiction, and it’s a legitimate form of philosophical criticism. When someone says “I cannot speak English” in English, we’re not “telling them what they believe” when we point out the contradiction. We’re identifying an internal incoherence in their position.

As for 1 Peter 3:15, you’re right to bring it up. That verse does call for gentleness and respect in apologetic engagement. But notice what comes before it in verse 14: “And who is he who will harm you if you become followers of what is good? But even if you should suffer for righteousness’ sake, you are blessed. And do not be afraid of their threats, nor be troubled.” Peter is calling believers to defend the faith with gentleness, yes. But he’s also calling them to fearlessly proclaim truth even when threatened. The gentleness Peter describes doesn’t mean avoiding hard questions or refusing to identify logical contradictions. It means maintaining respect for the person while challenging their ideas. Have I shown you disrespect personally? I’ve challenged your arguments vigorously. I’ve pointed out logical problems. I’ve used wit and rhetoric to make my points. But I haven’t attacked your character or your person. I’ve engaged with the position you’ve articulated and the arguments you’ve made.

If you feel I’ve misrepresented your position, then by all means, clarify it. But simply saying “you’re telling me what I believe” doesn’t address the actual argument. The argument is this: your moral language presupposes moral realism even while you claim to reject it. That’s not me telling you what you believe. That’s me identifying what your language reveals about what you actually believe, regardless of what you claim to believe. Here’s what would constitute honest engagement on your part: Answer the direct question I’ve asked multiple times. When you wrote that the Amalekite command is “by any standard of compassion or pro-sociality, an act of extreme cruelty,” were you: A) Making an objective moral claim that the command was genuinely wrong, or B) Simply expressing a personal preference that carries no more normative weight than your preference for certain flavors of ice cream? If A, then you’re not actually a moral non-realist, regardless of the label you apply to yourself. If B, then why should anyone care about your preferences, and why use such strong condemnatory language for mere preference expression?

You blocked me once rather than answer this question. You wrote elaborate debriefings declaring victory rather than answer it. Now you’re complaining about my lack of humility rather than answering it. At some point, Phil, the evasion becomes too obvious to ignore. So let me extend an olive branch here. You want me to ask rather than tell? Fine. I’m asking: Do you believe the Amalekite command was objectively wrong, or do you simply prefer that such things not happen? Do you believe my defense of it represents genuine moral deficiency, or merely different preferences shaped by different cultural conditioning? Do you believe genocide is actually evil, or just something most humans happen to dislike? Answer those questions directly, and we can have the honest engagement you’re calling for. Continue to evade them, and you prove my point about the unlivability of moral non-realism better than any argument I could make. The floor is yours.

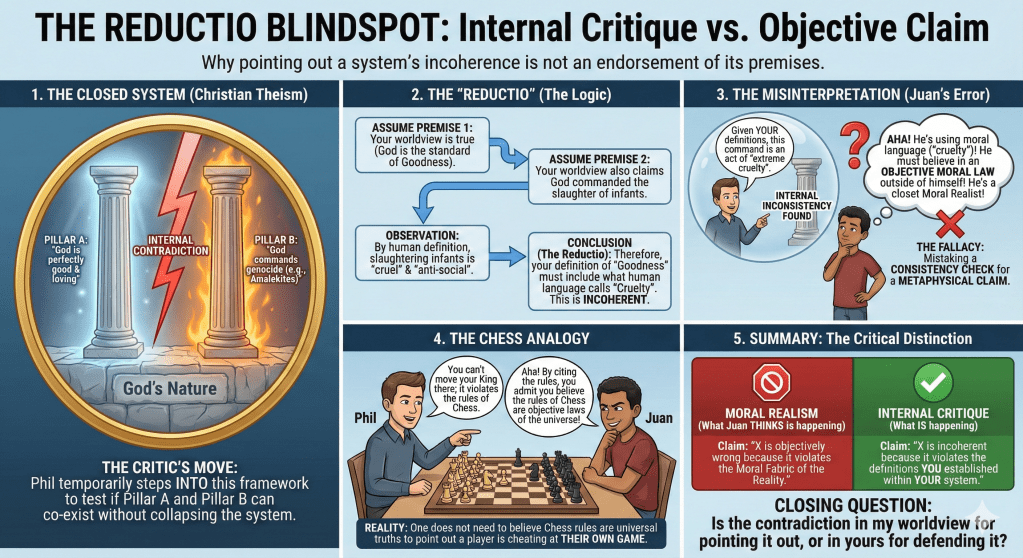

Here is an annotated list of the logical fallacies committed by Juan.

Overview of Juan’s Central Fallacy

The majority of Juan’s arguments rest on a single, fundamental error in reasoning related to how critics engage with worldviews they do not hold.

- The “Internal Critique” Misunderstanding (Straw Man / False Dilemma combined):Juan consistently mistakes Phil’s use of an internal critique (or reductio ad absurdum) for an objective moral claim.

- The Reality: Phil, as a moral non-realist, uses terms like “cruelty” descriptively, based on standard human definitions (e.g., “compassion or pro-sociality”), to point out contradictions within the Christian worldview (i.e., claiming God is “good” while commanding acts that fit the human definition of “cruel”).

- The Fallacy: Juan insists that using any evaluative language must mean Phil secretly believes in objective moral facts. He refuses to accept the third option: that Phil is provisionally adopting Christian definitions to show they are incoherent.

Detailed List of Fallacies

1. False Dilemma (False Dichotomy)

Juan repeatedly forces Phil into a binary choice between two options, ignoring legitimate third alternatives, specifically regarding moral language and discursive norms.

- The “Moral Language” Trap: Juan argues: “Either your outrage about 1 Samuel 15:3 was just you expressing personal discomfort (in which case, who cares?), or you were making a claim about objective wrongness… Because you can’t have it both ways.”

- Annotation: This ignores the option of descriptive conceptual analysis. Phil can identify that an act fits the dictionary definition of “cruel” without believing a cosmic moral law exists. Juan tries to force Phil into moral realism by denying the existence of descriptive moral language.

- The “Discursive Norms” Trap: When Phil calls for “honest engagement” and “humility,” Juan retorts: “If moral non-realism is true, then ‘honest engagement’ is just your preference… Your offense only makes sense if I’ve violated something objective.”

- Annotation: Juan assumes that rules of debate (humility, honesty) must be objectively binding cosmic laws to have any value. He ignores the pragmatic view that these are necessary functional rules for having a productive conversation, regardless of metaphysics.

- The “Grounding” Trilemma: Juan claims: “Either moral truth is grounded in God’s nature, or it’s grounded in nothing (your position), or it’s grounded in some abstract realm independent of God…”

- Annotation: This ignores vast swaths of secular moral philosophy (utilitarianism, social contract theory, virtue ethics, evolutionary ethics) that attempt to ground morality in objective ways that are neither “nothing” nor “God.”

2. Straw Man

Juan frequently misrepresents Phil’s actual position to make it easier to attack.

- Misrepresenting “Presupposition”: Juan opens by saying Phil wrote a post against ultimate justice “while simultaneously presupposing that it should [exist].”

- Annotation: Phil’s original post explicitly distinguishes between human desire for justice and the metaphysical fact of justice. Acknowledging a desire is not “presupposing” the object of that desire ought to exist.

- Caricaturing Moral Non-Realism: Juan constructs a six-point list summarizing Phil’s supposed position, attributing claims to him like “people who don’t care about justice are genuinely deficient.”

- Annotation: A consistent moral non-realist would not say someone is “genuinely deficient” in an objective sense, but perhaps “deficient according to shared social goals.” Juan attacks a confused version of non-realism that Phil hasn’t articulated.

3. Begging the Question (Petitio Principii)

Juan argues for God by assuming premises that are under dispute in the very conversation he is having.

- Assuming Objective Morality to Prove God: In his positive argument for God, Juan’s premises include: “Moral obligations that bind regardless of preference require a foundation…” and “Only God possesses those properties.”

- Annotation: Juan is arguing against a moral non-realist. Therefore, he cannot simply assume as a premise that “binding moral obligations” exist. He assumes the conclusion (that transcendent morality exists) in order to prove the source (God).

- Shifting the Burden to “Evolution”: Juan argues: “Evolution explains why we have the capacity for desiring justice. It doesn’t explain why that desire points to something real…”

- Annotation: Juan assumes the desire must point to something real and demands evolution explain that. He begs the question against Phil’s stance, which is that the desire doesn’t point to metaphysically real justice.

4. Ad Hominem (Circumstantial / Motive) & Bulverism

Instead of addressing the argument, Juan attacks Phil’s supposed hidden psychological motives or moral character.

- The “Suppression of Truth” Accusation: Juan quotes Romans 1 and claims: “You have the moral knowledge. You demonstrate it constantly. You just refuse to acknowledge the source because that would mean accountability. That’s not intellectual sophistication, Phil. That’s suppression of truth in unrighteousness…”

- Annotation: This is a textbook Ad Hominem Circumstantial, sometimes called “Bulverism” (a term coined by C.S. Lewis). Juan dismisses Phil’s arguments by claiming they are merely a psychological smokescreen to avoid “accountability” to God. He claims to know Phil’s inner mind better than Phil does, substituting theological accusation for philosophical counter-argument.

5. Weak Analogy

Juan uses analogies that do not hold up to scrutiny to support his “Argument from Desire.”

- The Hunger Analogy: Juan argues: “Every natural appetite corresponds to a real object: hunger to food, thirst to water…” implicitly comparing the abstract desire for “ultimate cosmic justice” to physiological survival mechanisms.

- Annotation: Hunger and thirst are immediate biological feedback loops necessary for an organism’s survival. A psychological desire for abstract concepts like “cosmic justice” or “immortality” is a different category of experience. The fact that biological needs have physical satiation does not prove abstract psychological desires have metaphysical satiation.

- The Mathematics Analogy: Juan tells Phil: “You’re like a man who insists he doesn’t believe in mathematics while using mathematical reasoning to prove his point.”

- Annotation: This fails because Phil is not using moral reasoning to disprove morality. He is using logical reasoning (the law of non-contradiction) applied to Christian definitions to show internal inconsistency.

6. Hasty Generalization (Argument from Desire)

Juan relies heavily on the idea that because a desire is universal, its object must exist.

- Comment: “…if every human who has ever lived desires justice… then yes, that’s evidence we’re tracking something real.”

- Annotation: While the universality of a belief can be a data point, it is a fallacy to assume universality equals truth (consensus gentium). Universal desires can also be explained by common evolutionary pressures or shared cognitive structures without requiring an external metaphysical reality corresponding to that desire.

7. Moving the Goalposts (Red Herring)

Juan shifts the topic away from Phil’s original point to avoid the force of the argument.

Annotation: Phil’s original post (Point 4) was specifically addressing the apologetic claim that God is necessary to guarantee ultimate justice in the end. Juan shifts the debate to a different topic: the grounding of moral values in the present. While related, it dodges Phil’s specific critique about ultimate outcomes.

Comment: Phil argued that natural laws explain why justice isn’t guaranteed ultimately. Juan responds: “Nobody’s claiming we need God to explain why bad things happen. We’re claiming we need God to explain why we’re justified in calling them bad.”

Leave a reply to J Cancel reply