This post now has a companion book called Coherent Apologetics. Check it out!

Would a Truly Compassionate God Condemn Honest Seekers?

— Introducing an Assessment of Christian Apologetics

Over the years, I’ve seen many Christian apologists insist that the evidence for their faith is so overwhelming that disbelief must stem from rebellion rather than reason.

To test that claim, I initiated a case study inside one of the internet’s most active forums for defenders of Christianity — the Facebook group Christian Apologetics, where hundreds of active members identify either as professional apologists, ministry leaders, or serious students of apologetic literature.

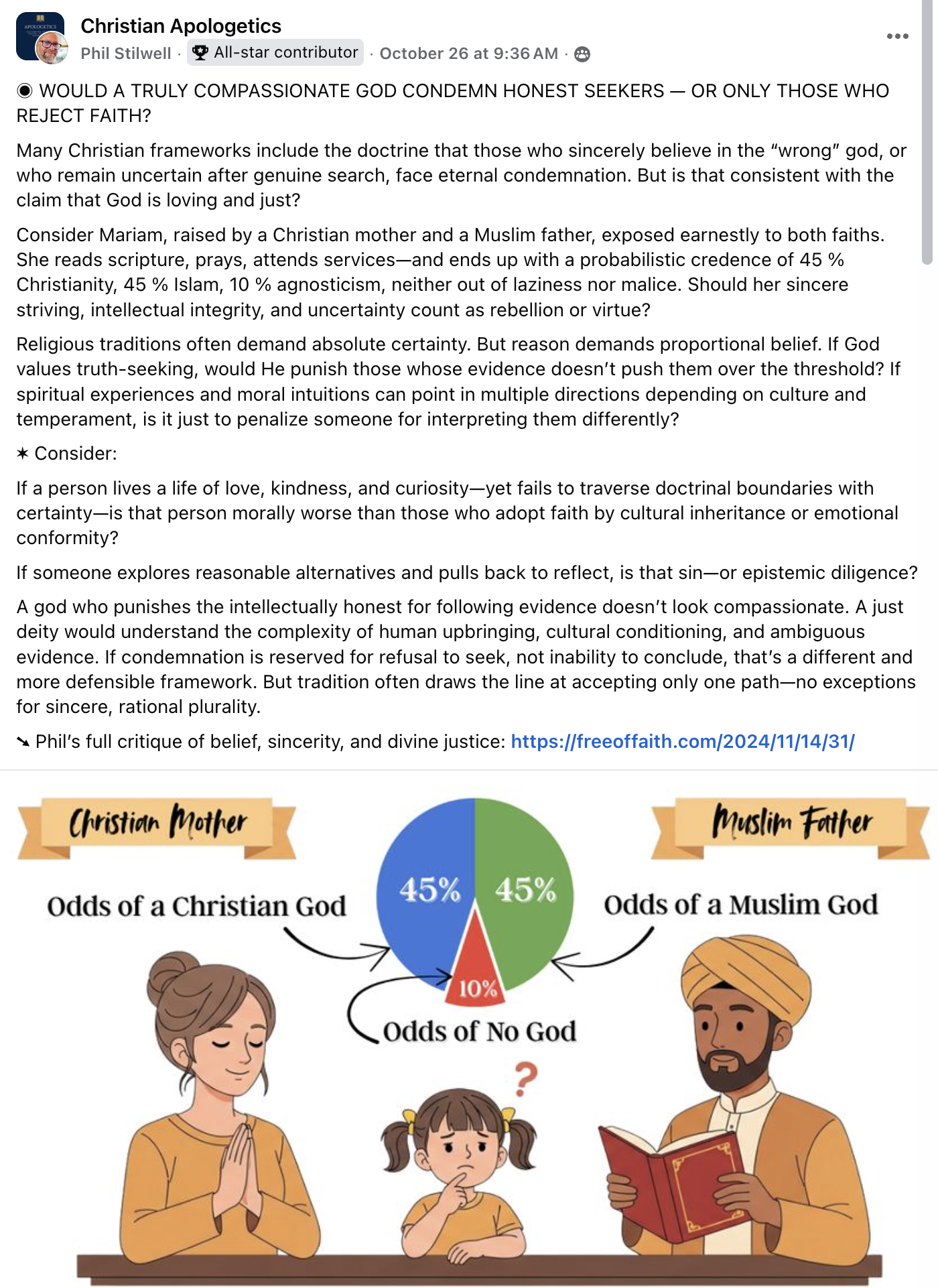

The question posed was simple:

Would a truly compassionate God condemn honest seekers — or only those who reject faith?

In that thread, I introduced a thought experiment about Mariam, a child raised by a Christian mother and a Muslim father. Both parents teach her earnestly; she reads, prays, and reflects deeply. By adulthood, she holds a probabilistic credence of 45% Christianity, 45% Islam, and 10% no God — not from apathy, but from the sincere difficulty of adjudicating rival truth claims.

If such a person died mid-search, would a just God condemn her for uncertainty?

The relevant Facebook post

Why This Series Exists

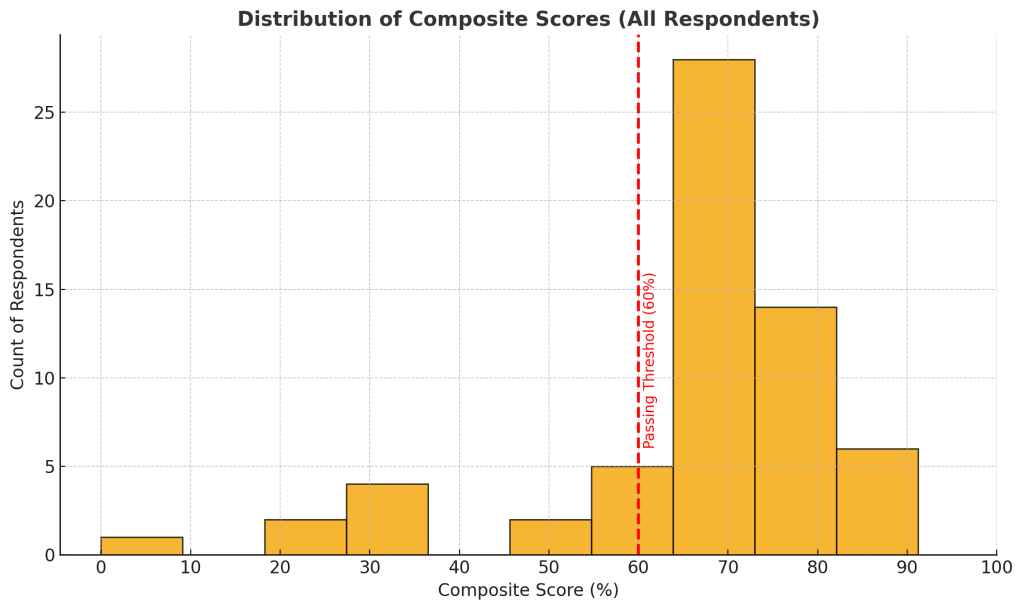

The responses to that question — from 63 self-identified Christians — formed one of the clearest real-world demonstrations of apologetic reasoning under pressure.

Each response was systematically assessed across ten analytic criteria: directness, logical validity, engagement with the question, theological consistency, empathy, and tone.

The results expose widespread training failures in how apologetics currently equips believers to engage epistemic challenges.

This series distills those findings for instructors, ministry coaches, and pastors. It is not an attack on Christianity; it is a diagnostic mirror held up to its reasoning practices.

What the Data Revealed

Even among articulate apologists, many responses fell into errors that should have been eliminated in the first semester of apologetics study:

✓ Failure to address the actual question — substituting emotion or evangelism for reasoning.

✓ Confusing epistemic fairness with divine omniscience — as though God’s knowledge alone ensures justice.

✓ Relying on “mystery” or “sovereignty” as conversation stoppers.

✓ Inconsistency — articulating “light-based” judgment, then denying its application in Mariam’s case.

✓ Evasion — offering comfort instead of content.

Composite scores (from the analysis table) ranged widely, but the pattern was clear: the median apologist struggled to provide a logically coherent defense of a just God under symmetrical evidential conditions.

In short, the problem isn’t theology — it’s reasoning.

Why Instructors Should Care

This assessment is not about “winning debates.” It is about improving epistemic responsibility within Christian education.

When students learn to answer such questions with clarity, consistency, and empathy for honest doubt, they represent their faith more credibly and reduce unnecessary harm to those genuinely seeking truth.

The full dataset — including respondent summaries, composite scores, and categorized mistake patterns — will be published in a sequence of pages that highlight:

- The 64 assessments (with individual feedback).

- The 20 recurring reasoning errors identified.

- Practical recommendations for apologetics educators.

An Invitation

I invite you to explore the pages in the series menu above, and consider whether there may be insights that will help you in your defense of the Gospel, if you are a Christian, or help you better address apologetic arguments, if you’re not.

A Final Note

Faith and reason need not be enemies — but when reasoning collapses, faith inherits its weakness.

This project invites Christian thinkers to face that collapse honestly, and rebuild apologetics on clearer epistemic ground.

For context, here’s the original discussion that sparked the assessment — the “Mariam” post that drew over sixty responses and inspired this evaluation.

(see “the relevant Facebook post above“)

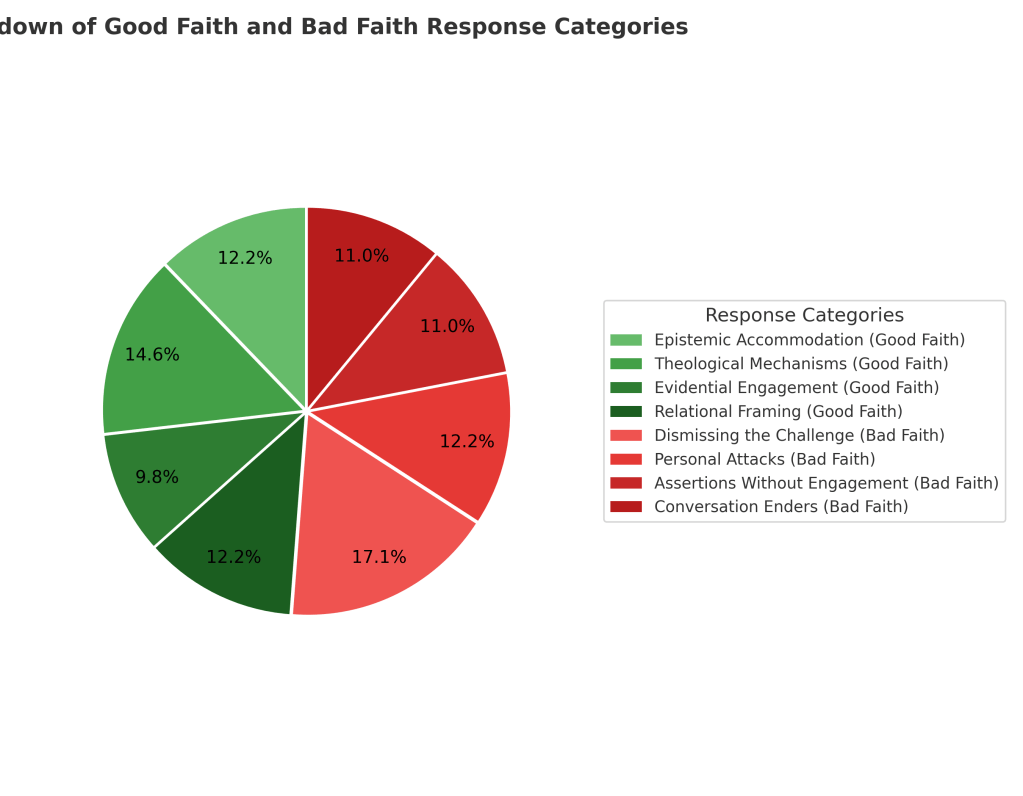

The two pie charts below show not just how participants differed, but how the conversations evolved. Many respondents began their engagement in good faith—honestly trying to reconcile Miriam’s situation with their concept of a just God. They showed curiosity, humility, and at first appeared willing to reason through the implications of their theology.

However, as the dialogue progressed and the logical consequences of their claims became harder to defend, many shifted tone and strategy. When pressed on contradictions—such as how an all-loving God could condemn a sincere truth-seeker who simply lacked epistemic access—open reasoning often gave way to defensiveness. Appeals to mystery, untestable assertions, and even personal attacks became more common.

This gradual turn explains why the two charts are not equally divided: the imbalance represents a pattern of retreat. The conversations didn’t begin in bad faith; they devolved into it as participants tried to shield doctrine from scrutiny. The data reveal how fragile apologetic reasoning can become when rational inquiry persists beyond the comfort zone of faith.

Other Relevant Charts

The Miriam Facebook Thread

The following analysis is drawn from a large Facebook discussion thread centered on a question I posed about Miriam—a hypothetical child raised by a Christian mother and a Muslim father, each sincerely convinced of their own revelation. (See “The relevant Facebook post” above.) This is found in the expanding section called, “The relevant Facebook post” above. The question was simple: If Miriam dies mid-search, which God would judge her—and on what epistemic basis?

What followed was a vivid cross-section of contemporary Christian apologetic reasoning in the wild. Dozens of self-identified believers responded, ranging from thoughtful theological reflections to defensive evasions, emotional retorts, and outright dismissals. The goal of this project was not to mock but to map—to categorize the modes of reasoning that emerge when faith claims are held against the standard of epistemic fairness.

By charting these responses into Good Faith and Bad Faith categories—and then further dividing them into eight subtypes—the analysis reveals the spectrum between rational engagement and conversational shutdown. The Sankey and pie charts visualize these gradients of reasoning, showing how frequently apologists abandon epistemic coherence when confronted with questions that threaten doctrinal certainty.

In short, this study illustrates that many apologists, despite claiming intellectual rigor, still rely heavily on rhetorical reflexes—faith appeals, personal attacks, or doctrinal assertions—to protect belief systems from scrutiny. The hope is that by exposing these conversational patterns, we can encourage more honest, evidence-proportionate, and logically coherent dialogue about claims that affect eternal stakes.

1. Good Faith: Epistemic Accommodation

These respondents acknowledge the epistemic challenge honestly. They don’t claim certainty about Miriam’s fate but emphasize humility, trust, and divine mystery. The underlying tone is one of intellectual restraint—they admit limits to human understanding and prefer to leave final judgment to God.

Examples:

✓ “No earthly authority holds the power or knowledge to judge these things. Jesus tells me to love her, so I will try to. I trust our God is good.”

✓ “You have no way of knowing how God would judge the little girl. Saying anything would only be speculation.”

✓ “It’s above our ability to accurately judge. God’s plan is perfect, and I have hope for everyone because of Jesus.”

2. Good Faith: Theological Mechanisms

These replies attempt to reconcile divine justice and human ignorance through doctrinal tools. They reference conscience, the law written on the heart, or the idea that honest seekers will find salvation even without explicit knowledge of Christ. These comments tend to be thoughtful, often citing scripture and theological precedent.

Examples:

✓ “God judges on what people know and how they react. Those who seek WILL find.”

✓ “Yes, I believe Miriam is saved in the name of Jesus even without knowing his name—like Old Testament saints.”

✓ “For when Gentiles, who do not have the law, by nature do what the law requires, they show that the work of the law is written on their hearts.”

3. Good Faith: Evidential Engagement

These interlocutors engage with the logic of the question directly. They treat faith as an epistemic issue and wrestle with the question of how evidence, uncertainty, and sincerity interact. Their focus is on whether belief formed under ambiguity could justly be a criterion for salvation.

Examples:

✓ “Truth is objective AND evidence can be ambiguous. If truth is objective, does your just God punish those who fail to locate it when the signals conflict?”

✓ “Faith is not our friend: if the method yields mutually exclusive revelations, the method itself is unreliable.”

✓ “What non-circular test lets a child in a split home decide which revelation is true before death?”

4. Good Faith: Relational Framing

Here, faith is described not as intellectual assent but as relational trust. These respondents stress sincerity, intention, and heart orientation rather than doctrinal accuracy. They assume a loving God judges by inward authenticity rather than external creed.

Examples:

✓ “God judges by the heart and sincerity, not the perfection of intellectual certainty or the quantity of evidence.”

✓ “Faith isn’t belief without evidence; it’s trust amid uncertainty. God honors sincere seekers who respond to the light they’ve been given.”

✓ “I trust our God is good! He proved it on the cross… I have hope for everyone because of Jesus.”

5. Bad Faith: Dismissing the Challenge

This category includes those who dismiss the question outright. They call it “hypothetical,” “insincere,” or irrelevant, avoiding any discussion of divine fairness or evidence. Their tone conveys irritation and a desire to protect doctrine from scrutiny.

Examples:

✓ “Hypothetical questions are just insincere in my mind, just someone trying to push for an argument.”

✓ “These are hypotheticals built around the individual. Salvation is a Monergistic work of God.”

✓ “Sounds like you’re just trying to avoid the finality that you have to make a choice.”

6. Bad Faith: Personal Attacks

These comments target the person rather than the problem. They accuse the questioner of pride, rebellion, or satanic influence. Rather than engaging the reasoning, they shift the focus to moral or spiritual character, often as a means to dismiss uncomfortable reasoning.

Examples:

✓ “You are a fool.”

✓ “You’re clearly trying to figure this out with your natural mind, and it’s a dead-end road.”

✓ “Intellectual honesty… is usually neither.”

7. Bad Faith: Assertions Without Engagement

This set of replies recites doctrinal slogans in place of reasoning. They quote verses like “Who are you, O man, to question God?” or “All have sinned,” but without addressing the epistemic or ethical tension. These comments use theological language to close the conversation.

Examples:

✓ “Either God is sovereign or he isn’t God. He has the right over the clay.”

✓ “She is without excuse.”

✓ “No one will get to heaven without His grace. What He does on that day is His decision.”

8. Bad Faith: Conversation Enders

These responses end dialogue entirely. They might appeal to prayer, divine mystery, or outright rejection of the question. The function is to reassert control or retreat from the conversation, signaling that rational inquiry has reached its limit.

Examples:

✓ “It’s faith. I can only pray that the Lord would show himself to you.”

✓ “It’s not up to you or me. God says the one who is saved is the one who places their faith in Jesus.”

✓ “God does what He chooses, so I don’t know how He will handle it… We will all appear before Him one day.”

Leave a comment